In the preface to the publication The scent of spiritual fragrance, timeless creations by Fotis Kontoglou, the scientific director of the Benaki Museum, George Manginis, describes the case of Fotis Kontoglou as “special” and therefore “difficult to decipher”.

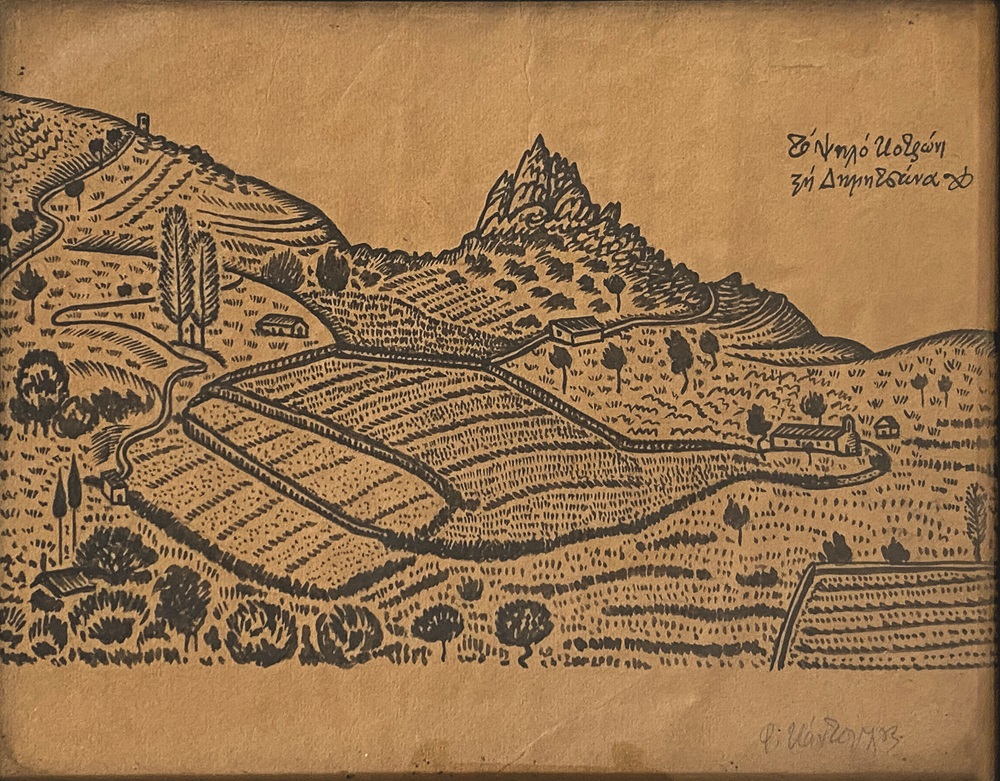

“How could these seemingly conflicting sides – the traditional craftsman and the modern creator, the one immersed in metaphysical doctrine and the one committed to the demand of progress – be bridged or reconciled?” This publication is a continuation of the 2015 edition of the Benaki Museum’s Fotis Kontoglou. From “Logos” to “Ekfrasis”.(edited by Christos Ph. Margaritis) and the Michael Asfantegakis study: A painting ‘Bible’ is revealed, Drawings and Sketches by Fotis Kontoglou in an album in a private collection. (Benaki Museum 2020). It is also an introduction to the events that will take place in 2025 on the occasion of the 130th anniversary of Kontoglou’s birth and the 60th anniversary of his death.

The present publication brings together and makes available to the research and generally interested public the results of research in galleries and private collections, which resulted in the identification of new, very important material: on the one hand, paintings by Kontoglou, some of which were little known and certainly unpublished and, on the other hand, many of his manuscript texts, also unpublished until today. The publication is structured in three parts:

Α. Contemporary approaches to the work of F. Kontoglou, B. Studying archives of manuscripts and drawings by F. Kontoglou, C. Rediscovering the painter F. Kontoglou.

The editor of the publication, Christos Margaritis, points out that the publication is part of a programme for the study of aspects of Greek religious art through the emergence of Greek hagiographers, which began in the 1990s, on the initiative and under the guidance of the late professors Angelos Delivorrias, director of the Benaki Museum and Nikos Zias of the Chair of Art History of the NKUA.

Kontoglou’s work, according to Margaritis, is multifaceted and his study is considered one of the “most important activities of cultural institutions and foundations”.

Demosthenes Davvetas compares the work of Fotis Kontoglou with that of C.P.Cavafy in that “they achieve the continuity of Hellenism through their artistic work”. He explains the uniqueness and originality of Kontoglou’s work, in which the Byzantine past and the modern spirit meet, the harmony of the coexistence of spirit and matter, freedom and institutions in an era of intense search for new balances.

Ioanna Stoufi-Poulimenou refers to Kontoglou’s translating and interpreting work on texts in the Bible and the Church Fathers with the aim of “building up his readers spiritually”. The texts, to which he devotes most of his literary and interpretive work, are ascetic and sober, with the main aim of demystifying reason, because “the deification of reason is slavery”, and the logical Westernized expression of the theology of his time. Similarly, in his visual work he will fight “everything Western in post-Byzantine and modern Greek ecclesiastical art” …. “Read the Gospel with a humble heart, and do not let it out of your hands, for the world has no other pillar that does not fall down…” It is worth noting his views on matters of icon theology as well. He considers “the need to preserve the continuity of sacred persons and scenes in Orthodox ecclesiastical painting, regardless of the artistic style of each creator”.

The surname Kontoglou, according to Eleni Skotinioti, refers to his mother’s family name, while in her text she also describes the “heavenly” environment he lived in during his childhood in Aivali. The writing of ‘Pedro Kazas’ would bring him close to the literary figures of the time, Ellie Alexiou, Galatea Kazantzakis and Nikos Kazantzakis. According to Skotinioti, “his literary production” can here be paralleled with his painting.Both as a hagiographer and as a literary artist, Kontoglou is a historian, and he mentions in detail his sources of inspiration and his textual works, in which his homeland, Ayvali, plays a prominent role. Reference is also made to the magazines Philiki Etairia (1925) and especially Kivotos (1952-1955), which he edited himself in collaboration with Vasilios Moustakis.

Christos Margaritis refers to the text by Angelos Sikelianos, dedicated to Kontoglou and his book “Pedro Kazas”, published in the newspaper “Eleftheria” in July 1951, shortly after Sikelianos’ death. Everything indicates, says Sikelianos, that Kontoglou is treading “on the path of the rugged Recursion” and “that by ascending as he is ascending, he will win – he has already won, we say – not the usual crown of some ‘glory’ but the secret crown of Love, which is received only by a genuine victor in Love”.

Maro Kardamitsi Adami refers to the interwar period in Greece, where the refugee Kontoglou matured artistically, and describes it as “optimistic, peaceful and modernist”. It refers to Kontoglou’s house in Galatsi, designed by the distinguished architect Kimonas T. Laskaris, influenced both by the mansions of Northern Greece and of Aivalius. The illustration of the house is described: “A mansion of Macedonia or a church porch”.

The frescoes from Kontoglou’s house are on display at the National Gallery, witnesses to the adventure of losing his home during the Occupation for a sack of flour. Dimitris Pavlopoulos presents and comments on three monumental paintings completed by Fotis Kontoglou in the 1930s, based on hard-to-find archival material. These are the frescoes he had painted in 1932 at his residence in the Kypriadou district with figures of his family and his mythology, the frescoes with figures of saints in 1934-35 at the chapel of St. Lucia belonging to the Zaimi family in Rio, Patras, and his frescoes in 1937-39 at the Athens City Hall, the route he proposes to take in Greek mythology and history.

Spyros Moschonas describes Fotis Kontoglou as a “modernist” who, together with Agenor Asteriadis, pioneered the revival of Byzantine art. He develops the circumstances that led the artist to act as a manager for the commissioning of ecclesiastical works in the period after the occupation, resulting in the painting of numerous churches in Greece and abroad, creating a peculiar “Kontoglou school”. As a teacher, he considered the thorough study of Byzantine monuments to be indispensable, ‘considering copying as a necessary process for understanding the tradition and for artistic maturation, which at the end of the journey would produce original works’. It is clear that the painter from Aivali had structured his workshop in the logic of a Renaissance bottega, i.e. a business.

Michael Angelakis points out the transcendental and surrealistic way of expression followed by Fotis Kontoglou, in order to serve the “liturgical” purpose of the icons “The purpose of the icon is not to unite the struggling Church with the Triumphant Church…”

Andromachi Katselaki notes that “Fotis Kontoglou is the one who consciously raises the issue of the ‘interpretation’ of Byzantine art ….he is aware that it is not only a stylistic idiom or a visual rendering of the uncompromising union of the two natures of Christ”. In his work Ekphrasis he writes and develops the codification of the rules governing Orthodox pictorial iconography.”

Christos Margaritis refers to the Archive of Neohellenic Religious Art of the Velimezis Library Collection and the works of Kontoglou included in it and the publication Ekphrasis, which was awarded by the Academy of Athens in 1960 and was published again in 1979 by the publishing house “Astir”, edited by Petros Vampoulis.

In her text “Fotis Kontoglou: the last anti-classical”, Nano Hadjidaki presents selected extracts from the text of the same title by Manolis Hadjidakis, which was published in the volume Kontoglou’s Memory (edited by Kostas E. Tsiropoulos in 1975). In his text Manolis Hadjidakis refers to the work of Fotis Kontoglou, to his ‘incomprehensible preference for narrow, unnatural figures … ugly faces, … not unpleasant, completely different”, to the need for a more “informed intellect” for the return of our national idiosyncrasy to a country devastated and humiliated by the Asia Minor Catastrophe, and places his work in the same historical need that founds the Benaki Museum, organizes the Delphic festivals, highlights the studies of Angeliki Hadjimichalis and G. Megas, expands the Byzantine Museum, etc. He considers that his influences as a hagiographer come mainly from the later Byzantine period, as he experienced it in the monasteries of Mount Athos and Meteora.

The second part of the publication is dedicated to the study, by Christos Margaritis and his team, of archives of manuscripts and drawings. The Library of Cornelius and Konstantinos Diamantouros, the Archive of Yannis Kontogiannis (S.P. Condon), the Archive of Maria E. Papadimitriou, the Archive of Neohellenic Religious Art, the Archive of the Holy Church of St. Dionysius of Areopagite and the Archive-atelier of Peter and Ioannis Vampoulis stand out.

Olympia Pappa refers to the Yannis Kontogiannis Archive with letters and texts written by Fotis Kontoglou (1946-1965) to his family friend Yannis Kontogiannis and his family, who were living in America.

Panagiota Katopodi refers to the hermeneutic part of Kontoglou’s work, especially to the Ascetic Discourses of Isaac of Syros, where exhortations and advice addressed to ascetics who follow a communal life are developed. Kontoglou’s main aim was to make the paternal texts, in a language that the reader could understand, ‘accessible to the people of post-war Greece and to give courage to those who are overwhelmed by the problems and difficulties of life’.

Dimitris Pavlopoulos, in a second article, presents the story of an unknown notebook of drawings by the artist, which comes from the collection of George D. Karanikolas, made in the period 1916-1917.

Maria E. Papadimitriou presents Fotis Kontoglou’s passion for the sea through his poetic and prose texts unknown to us. “An ancestral affliction that can only be discharged with words, with endless descriptions” and which certainly formed the basic motif of his fictional description, which was destined to write its own distinctive history.

Michael Asfentagakis mentions as a special section of Kontoglou’s work the private chapels that the artist has historicized, which he includes in a study he is currently working on. He starts from those published by Nikos Zias in 1991 and proceeds further.

Sotiria Kosma develops the artist’s iconographic approaches to the “Saint of Literature” Alexandros Papadiamantis, with whom “he shares the same values for Orthodoxy, ecclesiastical experience and expression”.

Christos Margaritis and Alexandros Makris present the Archive of Neohellenic Art and its activities, which refer to Fotis Kontoglou: “It is the continuation of the Velimezis Icon Collection and the Makris-Margaritis Anthograph Collection, as well as Collections of drawings, prints and images with 19th and 20th century material. The Archive includes working drawings, floral designs, models for temple buildings, as well as works by important Greek hagiographers and eponymous artists, mainly from the last two centuries.

The third part of the publication contains twenty original entries for twenty portable works by Fotis Kontoglou, belonging to galleries and private collections, for which no study has ever been made and for some of which only photographs or even a caption existed. The texts are signed by Michael Asfentagakis, Andromachi Katselaki, Maria Nanou and George Mylonas.

The last part of the publication “Light from Light” is dedicated to contemporary artists and their works inspired by Fotis Kontoglou’s creations: Stefanos Daskalakis, Markos Kambanis, Nektarios Mamais, Tasos Manzavinos, Nikos Moschos, Konstantinos Papamichalopoulos, Nikolaos A. Houtos.

From books by Fotis Kontoglou, publications and publications in general by Kontoglou or about Kontoglou, a selection of excerpts from his own works has been made, which we have recorded on the first pages of the texts, always with the approval of their authors.

Also presented are drawings by Kontoglou, published in his publications, such as PHILIKI ETAIRIA (which this year marks 100 years since its publication), KIVOTOS and various books of his, which adorn pages of the publication, especially the pages with the summaries of the texts in English.

The edition is extremely well edited, tight in meaning, holistic in its approaches to a multifaceted personality, such as that of the great Aivaliot creator. Influences and tropes in his material and intellectual surroundings are mentioned, from his “built and unbuilt” world. Although the artist himself was negative to any influence far from Greekness as a continuation of the Byzantine world, how can we fail to discern in his work contemporary and topical positions and affirmations, such as those of inclusion, equality , for example, when he paints “the five tribes of the earth”, according to Dimitris Pavlopoulos, and even in a “surrealistic approach to form”, which was, after all, always the aim of Byzantine art, as Maro Kardamitsi Adami comments in her text.

Leave A Comment