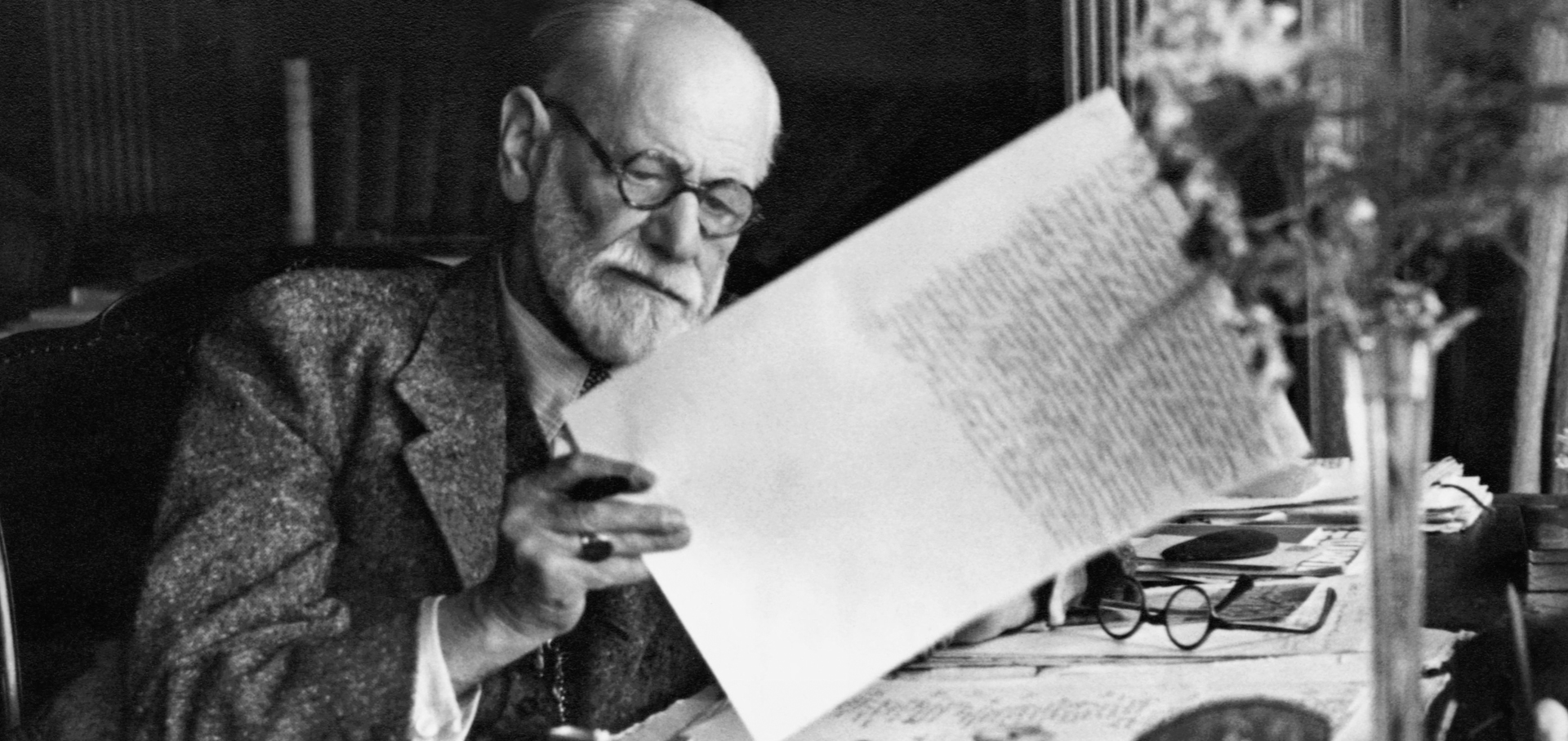

Fans of the father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), know that many elements of his personality and work are revealed by a visit to the last house he lived in, in London (20 Maresfield Gardens).

Freud Museum London

In this traditionally English house, which embraces the visitor as soon as he enters its well-kept courtyard, also lived until her death Sigmund Freud’s daughter and pioneer of child psychoanalysis, Anna (1895-1982). Four years after her death, the house was opened as a museum.

Visitors admire Freud’s private collections, his love for the figure of the Ancient Greek goddess Athena and of course his iconic study – whose aesthetic is a fusion of classical and oriental art.

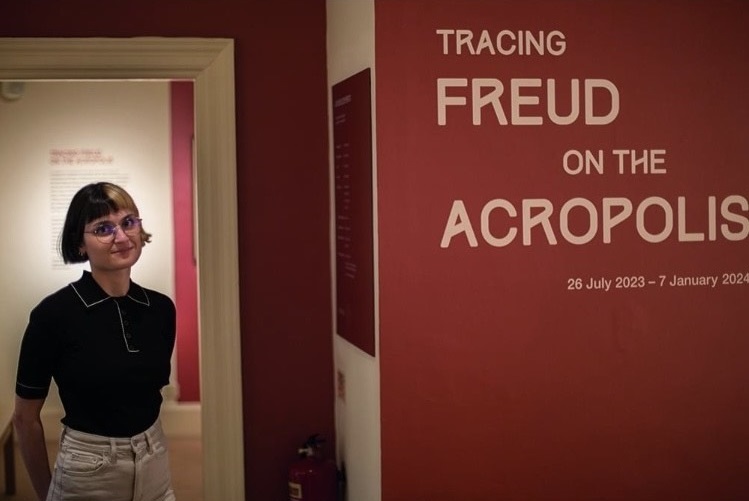

With the most recent exhibition hosted on the upper floor of the Freud Museum London, curator Marina Maniadaki, on the occasion of the visit of Freud and his brother Alexander to the Acropolis in September 1904, narrates the life relationship that the great thinker had with the elements of Ancient Greek culture. Tracing Freud on the Acropolis includes objects from Freud’s collection, travel correspondence, manuscripts, archival material and important photographs that document the Acropolis in the early 20th century.

Sigmund Freud

At the heart of this extraordinary exhibition – for which The Guardian has written praising comments – is the sense of amazement experienced by the father of psychoanalysis on the sacred rock of the Acropolis. His letter to the French writer Romain Rolland in 1936 reveals his feelings even many years later: “When, finally, on the afternoon after our arrival, I stood on the Acropolis and cast my eyes around upon the landscape, a surprising thought suddenly entered my mind: “So all this really does exist, just as we learnt at school!… It is one of those cases of “too good to be true” that we come across so often.”

The curator of the exhibition, which will run until the beginning of January 2024, was kind enough to show us around the Freud Museum London and offer us an exclusive interview.

The curator of the exhibition Tracing Freud on the Acropolis, Marina Maniadaki

The heart of the Freud Museum London is undoubtedly the study of the father of psychoanalysis. It is a room full of Freud’s archaeological treasures and his personal belongings (such as his chair and the couch on which he accommodated his patients). What can the aesthetics of these objects reveal about the character and habits of the great psychoanalyst?

Personally, I feel that Freud’s office is an almost dreamlike space, but at the same time heavy and very personal. The chair was a gift from his daughter, Matilda, and was designed by architect Felix Augenfeld specifically to accommodate the posture Freud took while reading – he liked to hold the book up while hanging one leg on the arm of the chair. In his library, which covers almost every wall, we find, among other things, illustrated volumes devoted to archaeology and art, with his notes in various places – perhaps, as a collector, he was looking for specific archaeological objects he had come across in the pages. Some of the archaeological objects in his collection were gifts from patients, friends and associates, and many were purchased on his travels and through dealers in Rome, Paris and Vienna. Freud’s way of relating to his collection was direct and personal. He greeted the wooden figure of the Taoist sage beside his desk, examined the marble figurine of the Egyptian god Thoth while sitting in the armchair next to the psychoanalytic divan, and curated the arrangement of the 2,500 objects covering almost every surface of the room. I’ll stop here – as there are actually many interpretations that can be made of each object.

The narrative of your exhibition Tracing Freud on the Acropolis revolves around Freud’s constant return to elements of Greek culture and the Acropolis. The exhibition room goes beyond the confines of the academic exhibition, it has an “openness” that invites the visitor into it. What was the criterion used to select the objects and manuscripts exhibited in the room on the upper floor?

The best known record of Freud’s trip to Greece in 1904 is the letter he dedicated to the French writer Romain Rolland three decades later. But there are also the postcards and letters he regularly sent to his family during the trip, his pocket notebook, as well as occasional references within his letters to friends and colleagues. The manuscripts presented in the exhibition are in the context of this very ‘tangible’ trace-record left by the journey. During the research, these records, combined with biographical references and the examination of Freud’s general relationship with Greece, created images that we tried to ‘locate’ in his collection of antiquities, in his library, and further archival material. As I mentioned above, he had a very special relationship with the books and archaeological objects in his collection, which directed us to think of them as parts of his relationship with Greece, and his experience on the Acropolis. Then, photographs of the Acropolis and Athens in the early 20th century, from the libraries of ELIA-MIET, Aristotle University and the British School at Athens, among others, as well as copies of objects kindly provided by the Acropolis Museum, completed the narrative of the exhibition.

The famous letter to Romain Rolland notes Freud’s sense of shock on the Acropolis in September 1904. At the same time, it is also a moment of self-psychoanalysis, as you noted in our tour. Can you elaborate further on your view of the significance of this letter?

In his letter to Romain Rolland in 1936, thirty-two years after his only visit to Greece, Freud describes his reaction when he reached the top of the Acropolis rock as disbelief and surprise. He never imagined he would make it this far. Freud attributes his feelings to guilt- by reaching the Acropolis, he had achieved more than his father, Jacob, who had limited education and financial means, and for whom the Acropolis could not have meant much. 1936 was the fortieth anniversary of Jacob’s death. Freud himself was now eighty, ill and unable to travel as when he was younger. As he says in the letter, his experience in Athens is something he thinks about more and more as he grows older. He reflects on how, as a child, he and his brother made the same journey every day, and how in 1904 they finally found themselves on the Acropolis, a journey he had until then considered ‘beyond possibility’. We could perhaps therefore consider this letter as a record of Freud’s actual and internal journey to Athens and the Acropolis from his childhood – an idea that played a role in the narrative flow of the exhibition.

Some of the objects in the exhibition were loaned to you by the Acropolis Museum. What are the procedures that an exhibition curator has to follow in order to achieve a loan of objects between two museums?

The Acropolis Museum kindly provided us with faithful copies of two very special objects from their Collection, made by the team of conservators in their workshop. The loan procedures, which we did, for example, for the 1904 travel guide to Athens from the Warburg Institute, are a little different. At the first stage a letter is written outlining the curatorial context of the report, and the loan dates. Together, various practical information is submitted in relation to the conditions of the object’s display, from the environmental parameters of the exhibition venue to the type of display case, and arrangements are made for the transport of the objects. These requests shall be submitted at least one year before the start of the loan period. The physical condition of the object, its value, as well as its role in the permanent exhibitions of the museum to which the request is imposed, all play a role in whether it will be approved.

Are there any plans to host this exhibition at the Acropolis Museum?

There has been no discussion about presenting the exhibition in Greece.

It is a special honour for our country that qualified people like you are curating exhibitions of international scope. What are your next steps in the sector of exhibition curation?

I am very interested in the way we relate to our family history and the past, especially in the context of migration and our constant reintegration into new cultural and personal contexts. I have recently started working at the Museum of the Home in East London, which focuses on the concept of home and how we interact with it through a programme of temporary and permanent exhibitions. At the same time, I am working on some personal projects that I hope to present in Greece.

Ιnformation about Freud Museum London and Tracing Freud on the Acropolis

Tracing Freud on the Acropolis

The Freud Museum, 20 Maresfield Gardens, Hampstead, London NW3 5SX.

Dates: 26 July 2023 – 7 January 2024. To book tickets please visit www.freud.org.uk

Opening Hours: 10.30am – 5pm, Wednesday to Sunday.

For more information you may visit: www.freud.org.uk |020 7435 2002| or [email protected]

Leave A Comment