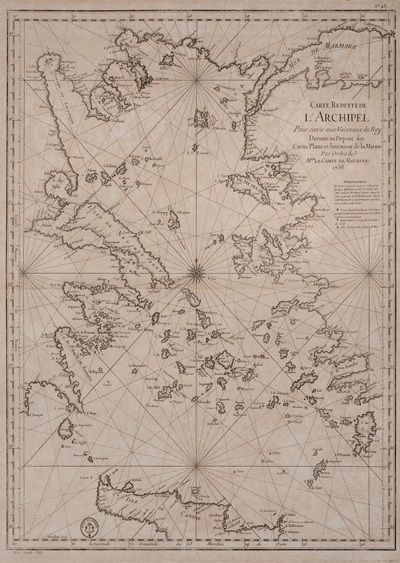

Piracy has been an economic activity since ancient times. The Mediterranean had a developed commercial economy and shipping. However, the shipping routes followed by merchant ships were close to the coast due to the dangers of sailing on the open sea. The morphology of the Mediterranean coastline provided an ideal environment for the development of piracy. The fast, light pirate ships could remain hidden on the coast and charge at merchant ships. The inhabitants of coastal settlements, who had small boats for local trade, fishing, and travel, could easily turn to piracy for additional, easy income. These were probably the first pirates as early as the third millennium BC.

Ο Διόνυσος και οι Τυρρηνοί πειρατές / Dionysus and the Tyrrhenian Pirates

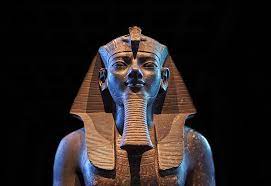

The phenomenon grew in magnitude and was apparently better organized, as in the middle of the 2nd millennium Pharaoh Amenhotep III took measures to defend against “naval raiders”.

Amenhotep III

Throughout antiquity, the phenomenon was never absent and continued to pose a threat to trade. Pirates organized themselves into large groups, collaborated with kingdoms and empires of the time and established bases in the Mediterranean. Antikythera was one of them.

Despite their strategic position on the sea routes leading from Crete, the Aegean and the Black Sea to the Western Mediterranean, in the Peloponnese Antikythera was inhospitable due to aridity and almost throughout the period of antiquity remained almost uninhabited. There are only a few references to Aegilia, which was the ancient name of the island.

However, the morphology and location of the island was ideal to attract pirates. The existence of a “hidden” harbour in the island’s sheltered bay, the inaccessible interior of the island and of course its strategic location brought pirates to the island and they settled on it, establishing a base.

Γναίος Πομπήιος ο Μέγας / Pompey the Great

The pirate presence on the island is related to the destruction of the Persian state by Alexander the Great. The areas of Crete that had been subjugated to the Persians were left unprotected and turned to piracy, with the main objective being the commercial activity of Rhodes. It therefore appears from a settlement created in the 3rd century that the same pirates had established a base in Antikythera.

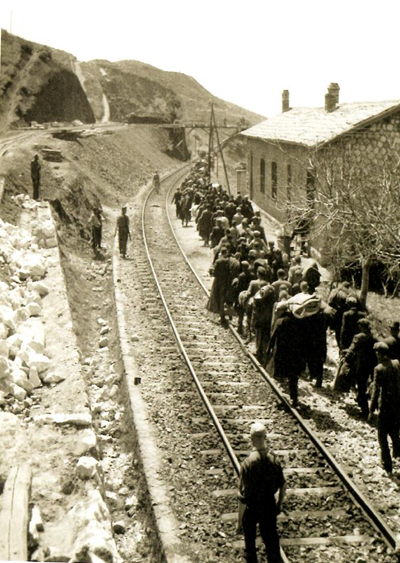

Pirate bases, not only in antiquity but also in modern times, had fortified positions as the lives of pirates were constantly under threat. They had to protect their booty and defend themselves against attacks by competitors and naval forces seeking to destroy them. In Antikythera, the wall of a Hellenistic castle is preserved in a fairly good condition and was of course used by the pirates. The discovery of many arrowheads, spearheads and other weapons, projectiles from catapults and the roughly repaired wall in some places, proves that the pirates’ den was the target of attacks. In fact, archaeological finds indicate at least one Rhodian raid on Antikythera in the 3rd century BC.

Antikythera continued to be a pirate base for about 250 years. Piracy continued to plague the eastern Mediterranean throughout the Hellenistic period with Crete being a key base.

The pirate presence ended in the first century BC. In 67 BC Pompeius succeeded in wiping out the pirates in the Mediterranean by undertaking several operations against them, killing thousands and giving privileges to those who swore allegiance to Rome.

In the small but very beautiful Archaeological Museum of Kythera there is an exhibit that tells us a strange story, at least from today’s point of view. It is the tombstone of Philinna, with the inscription “Philinna Eupolemos Myndias”. She was an educated woman of aristocratic origin from Myndos in Asia Minor, one of the cities of Caria on the peninsula of Halicarnassus, which from 129 BC was part of the Roman Empire.

Επιτύμβια στήλη Φιλίννας. Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο Κυθήρων / Tombstone of Philinna. Archaeological Museum of Kythera

She chose to be depicted on her tombstone holding scrolls precisely to emphasize her intellectual culture and to be remembered by future generations. Her family was obviously wealthy as they had provided for their daughter’s education. But what fate brought this woman to the island of pirates? Did she follow her merchant or officer husband to this inhospitable land? Did she long for her home in Asia Minor when she was studying at her residence in Antikythera? We may never know. But surely Philinna would have had a fascinating life to talk to us about…

Sources

Σαμαράς Ευάγγελος, Νησιωτικοί οικισμοί και θαλάσσιοι δρόμοι: μια μελέτη οικιστικής για τις Κυκλάδες (1200-700 π.Χ., Διδακτορική Διατριβή, 2017

http://antikythira-enosi.gr/images/pdf/anaskafes.pdf

https://www.worldhistory.org/Piracy/

https://www.kathimerini.gr/culture/222374/to-antro-ton-peiraton-sta-antikythira/

Leave A Comment