Physical pain, the concepts of healing, and the opening of new horizons in the field of medicine are themes we trace in literature as early as the time of Homer. What else, if not an early exercise in narrative medicine, does Odysseus’ encounter with his mother Anticleia and their dialogues about illness, fate, and death from grief remind us of? Similarly, in “Plutus,” Aristophanes highlights through storytelling and satire the importance of antidotes (which pharmacists would place inside citizens’ rings for immediate response to a serpent attack), as well as the vital contribution of art in addressing health crises at the Asclepieia.

Over the centuries, the imagination of writers has galloped ever further, with Jules Verne (“From the Earth to the Moon”), Mary Shelley (“Frankenstein”), and more recently Alasdair Gray (“Poor Things”) and Richard Powers (“Bewilderment”) starting from realism and historicity, moving toward literary narratives that intertwine imagination with social commentary and innovation in science.

In contemporary publishing, there is indeed a noticeable shift towards modern methods of narrative medicine, especially in literary works that depict the science of medicine in various ways on their pages.

In 2024, the internationally acclaimed Greek director Yorgos Lanthimos brought to the big screen the surreal work of Alasdair Gray, Poor Things , awarding Emma Stone her second Oscar. The novel, written in 1992, is now published by the Greek publishing house Ellinika Grammata and is in its 12th edition, translated by Dimitris Vourdoulakis. Alasdair Gray bases his work on the great literary tradition of the Anglo-Saxons, using science fiction in a way that directly communicates with Mary Shelley and creates a series of nightmarish images reminiscent of Lewis Carroll’s darkest fairy tales. The central characters are Godwin Baxter and Bella—Baxter discovers the body of the beautiful young woman and attempts to break the boundaries of biology by bringing her back to life. Gray avoids didacticism but sharply critiques the morals of the era, especially patriarchal stereotypes perpetuated through representatives of medicine, law, and philosophy. Identifying female emancipation with the exploration of sexuality, Gray uses sketches, fictional letters, and the technique of pastiche to offer a work full of imagery and reflection on the ethics of science.

/s3.gy.digital%2Fpediobooks%2Fuploads%2Fasset%2Fdata%2F1701%2Fpoor-things.jpg)

A peaceful revolution of patients for empathic care with kindness is envisioned by Mayo Clinic Professor of Medicine Victor Montori in his work “Why We Revolt” (brought by University Studio Press). Deploring the greed, ambiguity, and burden that industrialized health care places on physicians and patients alike, Montori focuses on the concepts of humanity, elegance, inclusiveness, and the bravery required to overcome the problems of modern health care systems. Spare, full of examples of exemplary narrative medicine, Montori’s work creates feelings of hope in the common man and redefines the physician’s relationship to the essence of his or her science.

“Is it literature that makes use of medicine, or is it medicine that makes use of literature? What is it that makes them attract each other, repel each other, or relate to each other?” These are just some of the questions posed by Massimo Peri in his work Sick with Desire, published by the Crete University Press. Starting from Erotokritos by Vincenzo Kornaros, the profound scholar of both classical and medieval Greek literature undertakes a deep dive into the psychopathology of love as it is revealed in the adventure of Erotokritos and Aretousa. At the same time, Kornaros emerges as a knowledgeable figure of Aristotle and medieval medicine, ultimately siding with poetry. The great poet attacks medical thought with its own weapons, calmly and clearly describing the story of a rational therapeutic treatment that is by definition doomed to fail. Fate and providence, from the works of Ovid and Shakespeare to modern melodrama, are for the narrative the only elements capable of healing the sufferings of love and the marks it leaves on the soul and body of mortals.

Fredy Gessed, in The Salt of Madness, returns to a poetry of heteronyms, a prose poetry that runs through Dante to culminate in a Beckettian cry. “It is clear that God has escaped from my skull. He left behind traces of blood,” confesses Ariel Müller in the preface of the poem, published by Patakis Publications in a translation by Agathi Dimitrouka. Essentially, it is a plunge into the mind of a male intellect that is ill and ultimately discovers his own Beatrice in the person of psychiatrist Dalsotto. This is a groundbreaking depiction of psychopathology on paper, as the poet confesses that the psychiatrist “was the first to suggest I write the ‘white monologues,’ as I called those voices in my mind.” The stages of therapy, the creative outbursts that provide the raw material for the work, make The Salt of Madness a small masterpiece for every seeker of Latin American poetry.

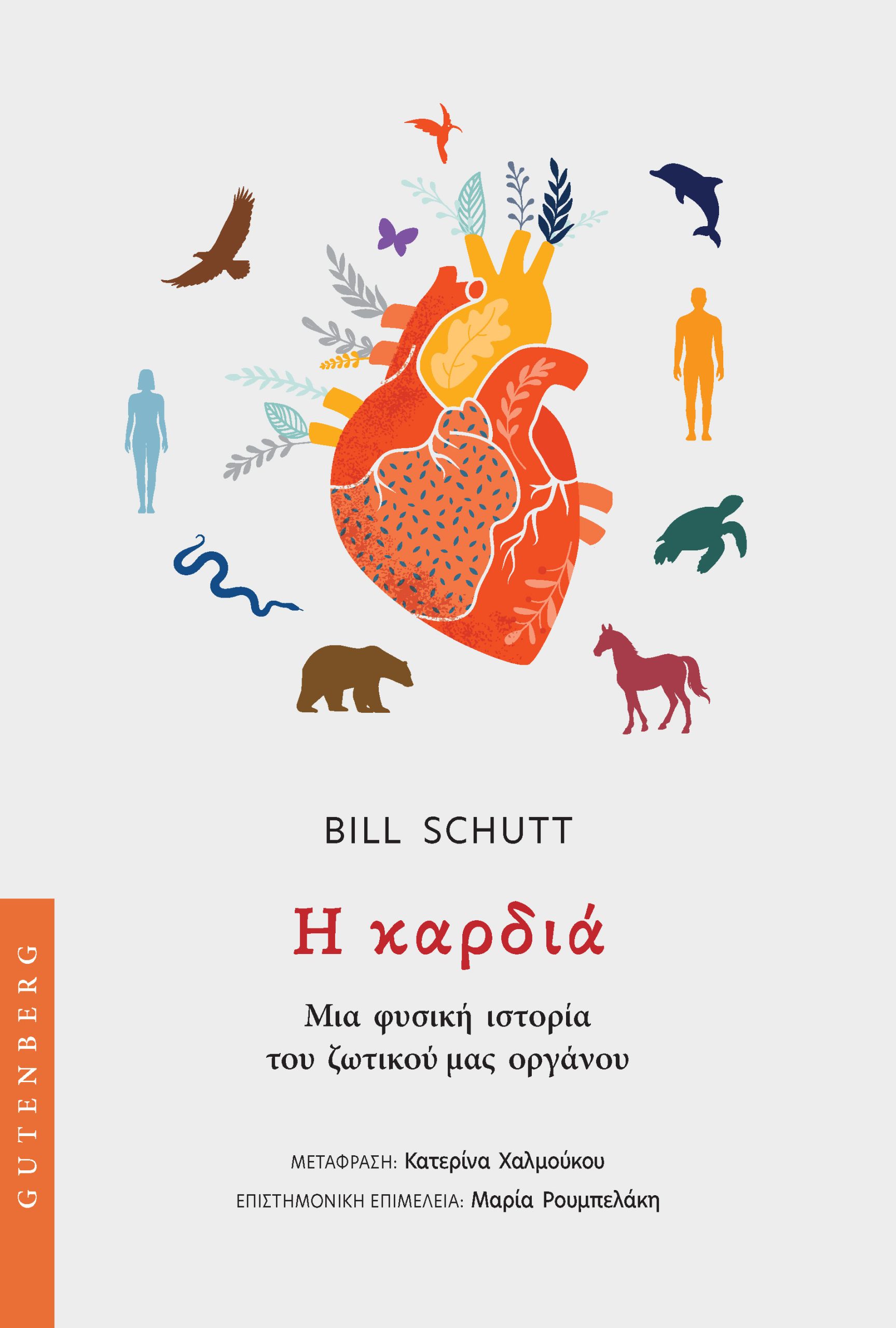

Are you interested in explorations around Natural History? Do you want to learn everything about one of our most vital organs, the heart, without feeling melancholic? Then you should turn to Bill Schutt’s book Pump: a Natural History of the Heart, published in a particularly well-crafted edition by Gutenberg Publications. Bill Schutt’s work is a compendium of storytelling in biology and medicine through vivid and sometimes humorous narration. The anthropologist from the American Museum of Natural History traces the history of the heart across various species, from bats and fish to humans, and approaches the philosophical reflections of the ancient Greeks and Egyptians who believed the soul resided in the heart. “At the end of this journey, you will have a renewed appreciation for the crucial role of the heart in the natural world and in the world of humans, as it is both a machine that drives the circulatory system and a mysterious organ at the core of human civilization and human nature,” notes the author in his preface. If his main goal was to forever change the way we perceive these matters, then with such an original and vivid narrative, he certainly succeeded.

The SOS Doctors and Papazisis Publications make a significant contribution to the understanding of the field of narrative medicine by delivering to the Greek audience the academic work The Principles and Practice of Narrative Medicine. Written by some of the most respected and pioneering founders of narrative medicine, as taught since 2009 in the corresponding postgraduate program at Columbia University in New York, it is primarily aimed at medical students as well as doctors seeking to sharpen their empathy. Indeed, in her introduction to the work, Rita Charon defines the field of narrative medicine and argues that it “began as a theoretical and practical scientific discipline aimed at rigorously enhancing medical care by improving doctors’ ability to skillfully absorb the stories patients tell about themselves.” Drawing from narratology, European philosophical currents, and postmodern theory, narrative medicine places the patient-doctor dyad at its center. On one hand, doctors are encouraged to appreciate the importance of emotion and the intersubjective relationship created through storytelling in the clinical context, while patients, through their participation, achieve smoother communication with medical staff, inclusivity, and justice in medical care.

Orthopedic doctor Giorgos Dendrinos, in his new book Oh, My Back! The Magical World of the Herniated Intervertebral Disc (Patakis Publications), speaks with a distinctive humor about one of the most common problems of modern humans: spinal disorders, without trying to sugarcoat the issue. With illustrations by Giannis Kouroudis vividly accompanying the chapters, this book employs the charm of storytelling to bridge in an unprecedented way the once wide gap between doctor and patient. Drawing on the principles of narrative medicine, Giorgos Dendrinos is accessible to a broad audience and enriches the work with numerous references ranging from the Parthenon and Shakespeare to classic Greek cinema. Unafraid to explore the unknown, he concludes with Hippocrates’ saying that “Sometimes doing nothing is a good treatment”—an idea that can apply both in medicine and more broadly in life.

If we wanted to take a breath from books dealing purely with medical and therapeutic issues through storytelling, there would be nothing more ideal than to turn to the multi-layered universe of Emilia Hart. Already winning recognition from critics and the public, her first novel, Weyward (translated in Greek by Christina Sotiropoulou and published by Kleidarithmos), unexpectedly weaves together the stories of three women in different historical periods as they struggle to cope with hostile, abusive environments haunted by memories. Beyond the feminist perspective on intergenerational trauma, Emilia Hart, through the character Altha, refers to the early medical practices of the Middle Ages that led the heroine to be persecuted in 1619 on charges of witchcraft. The compassionate nature of the woman contrasts with the ruthless patriarchal environment, and nature emerges as ever-present and empathetic to Altha’s suffering: “They lifted me onto the cart with great ease, as if I weighed nothing at all. The mule was a poor creature—it looked as if it were starving like me, its ribs protruding beneath its dull coat. I wanted to reach out and touch it, to feel its pulse beneath its skin, but I did not dare.”

For those interested in exploring the relationship between psychotherapy and narrative practices, the most appropriate work is Alice Morgan’s easy-to-read (as its subtitle suggests) introduction, “What is narrative therapy?”, published by University Studio Press, translated in Greek by Adam Harvatis and edited by Violeta Kaftantzis. Having dedicated her work to the core of family relationships, Alice Morgan through narrative therapy deconstructs the traditional role of the therapist, focusing on the cultural specificities and uniqueness of each person in the self-therapeutic (now) journey of psychotherapy. Narrative practices include externalizing problems, reintegration discussions in memory, writing therapeutic letters, using rituals, partnerships, reflective groups, and more.

Through his flawless, bibliographically documented treatise, Kostas Kostis takes us to In the Time of the Plague (Crete University Press). A many-years-long research led to the writing of a book from which, according to Kostis, the reader can expect “an attempt to depict certain situations centered around a disease, proverbial for the destruction it caused in other societies and other times.” Drawing on sources spanning centuries, Kostas Kostis seeks to understand the deeper causes, worldviews, and cultural mentalities that led to the outbreak of the pandemic in the 14th century, while also exploring the modern, often inadequate infrastructure that leaves millions of present-day inhabitants of India defenseless against the plague.

Handball champion and global citizen Anna Psatha makes a return to the roots of humor through her adult fairy tale The Handbook of Good Pain (Kedros Publications). Without didacticism and with a narration so lively and montage-like that it might make you finish the book in half an hour, Anna Psatha shares personal moments of her physical pains, asthma attacks, but above all a way of thinking that will convince you to see life differently. Because no matter how “similar” some stories may seem to our own, there is always “another way to look at life.”

Alexandria Publications bring us into contact with some of the most fascinating pioneering texts in anthropology through the publication of four lectures given by William Rivers in 1915-1916 at the Royal College of Physicians. The book Medicine, Magic, and Religion represents an early, almost psychoanalytic attempt to interpret the thoughts and ideas expressed in Primitive Medicine. As G. Elliot Smith notes in his foreword, “The fundamental purpose of primitive religion was to ensure life, which it achieved through certain simple mechanical procedures based on logical inferences but often mistaken premises. Primitive medicine sought to achieve the same goal, and naturally used the same means. That is why the origins of religion and medicine share a common matrix, of which magic was simply a particular part.”

From the creative imagination of the always scientifically restless Richard Powers emerges a novel of incredible precision and emotional intensity, Bewilderment (translated in Greek by Giorgos Kyriazis, published by Gutenberg). The protagonist is Theodore Burn, an astrobiologist trying to cope with the loss of his wife as well as the challenges faced by his ecologically sensitive son Robin, who is on the autism spectrum. Divided into short but densely written chapters, this work could serve as a source of inspiration and an exercise in empathy for those reflecting on the concept of narrative medicine. Powers rejects a stereotypical treatment of his subject and lets his imagination run wild, especially when recounting the adventures on the imaginary planets created by Theo and Robin. However, this is not merely a literary device, as the conditions the characters encounter on each planet, along with its features and creatures, dramatically reflect the evolving phases of their relationship. A father’s love reaches the negation of ego and absolute devotion. “Nobody wants to be alone, Robbie.”

As previous examples have shown, doctors and scientists can often move us deeply with their stories—even change our lives. Dr. Satchin Panda of the University of California, San Diego, through a playful narrative with references to our daily lives, promises to synchronize our biological clock by discussing the famous “Circadian Code.” His revolutionary handbook, published in Greek by Kedros Publications, teaches us that there is an optimal time to eat in order to burn calories during sleep, as well as the right times for exercise, rest, and peak productivity during a workday. The Indian scientist, by emphasizing simple things like when to eat and when to expose ourselves to natural light, helps us prevent or delay the onset of diseases.

With the recent coronavirus pandemic, lovers of modern Greek literature returned to one of its greatest chapters, Alexandros Papadiamantis, and one of his most powerful short stories, Vardianos at the Sporca. This story, which uniquely highlights the impact of the cholera outbreak that struck Europe in 1865 and the measures taken by the then Greek government, can be found in the beautiful hardcover edition published by Estia Bookstore (which also includes Chalasochorides, O Tiflosourtis, Navagion Navagia, I Nostalgos, and I Daskalomanna). Written in 1893 as a serialized story for the newspaper Akropolis, the tale narrates the story of the old woman Skevos who disguises herself as a guard in order to save her child, who remains in quarantine at the improvised plague hospital on the island of Tsougria. The Guard at Sporka captures the local society of the time, the dialect, and the superstitions, often resorting to a subtle irony with shades reminiscent of Dostoevsky.

The award-winning Rumena Bužarovska, one of the most recognized voices in contemporary women’s literature, courageously explores the impact of patriarchy on women through the short stories included in the collection I’m Not Going Anywhere (Gutenberg Publications, translated in Greek by Alexandra Ioannidou). Beyond the collapse of the traditional family, Bužarovska often identifies the remnants of patriarchy in the way women look at each other. Most notably, the opening story of the collection, Tina’s Problem, takes us to Tina’s first, quite traumatic visit to the gynecologist. With a style akin to the raw realism of Rachel Cusk, Bužarovska reconstructs the threatening gaze of the world upon Tina’s privacy in a brief story that should be included in every manual on narrative medicine, as it vividly addresses the relationships between patient and doctor as well as among patients themselves in waiting rooms.

Have you ever wondered what the meaning of life is? Does God exist? Are we truly free? What happens when we are no longer here? These same questions occupy the distinguished behavioral neurologist Jay Lombard, whose work The Mind of God: Neuroscience, Faith, and the Search for the Soul is published by the always scientifically oriented Pedio Publications. In fact, as Patrick J. Kennedy notes in his extensive foreword, Dr. Lombard seeks to unite people, different perspectives, and explanations regarding the eternal questions of our species. The neurologist, through his sober yet captivating narrative, attempts to reprogram our brains and reminds us that we can collectively join forces and confess without shame that we all experience pain. Lombard’s most significant contribution to the dialogue, of course, is his admission (from the very first chapters of his book) that science is not the only truth, but that truth can also be found in philosophy, literature, music, art, and history. Breaking taboos, the famous neurologist emphasizes the importance of balance that arises both from the measurable aspects of science and the transcendence of faith.

/s3.gy.digital%2Fpediobooks%2Fuploads%2Fasset%2Fdata%2F1691%2Fo-nous-tou-theou.jpg)

Leave A Comment