Certainly, details. Because no one can, nor is allowed to speak about beauty holistically, in an authoritative manner. Only through hints. Or fragments. In other words, half-spoken words. In contrast to loss. Where words abound. Or rather, where everyone has experienced it so deeply, that words are unnecessary. Perhaps just a sigh is enough. Just that.

On the other hand, beauty is always something related to the past. And that’s why our relationship with it is exhausted, not so much in experiencing it—this is reserved for the initiated—but rather in its idealization. In nostalgia. This is what we can endure as humans. To then face the mourning of loss. For what we have destroyed with the lethal innocence of children. A state we have all experienced. In this city, in this country. Forgetful of our history, ungrateful to our own tradition. As children, we destroyed our toys to learn. As adults, we destroy, out of despair, what surpasses us. Without learning anything. To forget, to erase what we knew. Loss as oblivion and poison as medicine. Laestrygonians who do not remember. Not only us, but those who come after us too. So that beauty becomes, instead of testimony, torment, and instead of pleasure, pain.

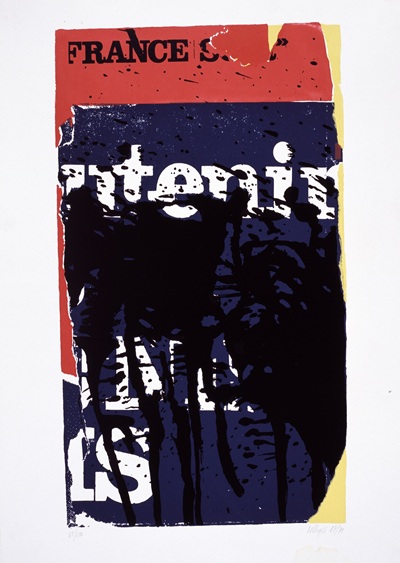

Tassos Vrettos

These things are known to all. Like the way we ostracized the classical tradition that was nourished in our soil for millennia. Because neoclassicism in Greece was never a romantic fantasy as it was in the rest of Europe—a Greek revival, a neoclassicism—that is, the ghost of the classical and the elegy of its loss—but something native, resurrected in the most natural way. Like the olive pit that finds ways, though subterranean, to come back into the light. This light that resurrects can be seen in the façades of Ziller’s neoclassical buildings, as depicted by Tsarouchis.

Neoclassicism in the rest of Europe, around 1800, was yet another version of the explosive movement called Romanticism, or if you prefer, it was the disciplined, rational management of romantic passion. The common reference of both—Romanticism and its alter ego, Classicism—was the nostalgia for the past. Only that the Romantics longed for the Middle Ages, while the Classicists for antiquity.

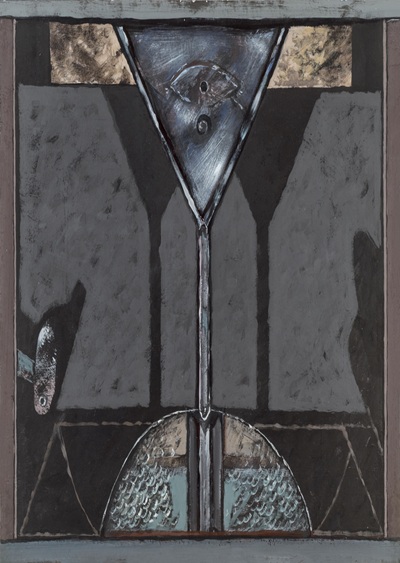

Yannis Tsarouchis, The Empeirikos Mansion, 1959

Immediately after the liberation of the small Greek kingdom—essentially a protectorate of the great powers—the historical context allowed mythical figures of European Romanticism to become involved in the building of the new capital: Schinkel, the teacher of Kleanthis-Schaubert, Klenze, the Danish brothers Hansen, Boulanger, Garnier, Lange, Gärtner. And of course, the great Ernst Ziller, who dominated the reconstruction of the capital for more than half a century. Initially as a contractor for the construction of Hansen’s Academy, and later as the exclusive architect of kings, prime ministers, and the entire bourgeois class, not only in Athens but also in many other cities across the country, from Patras to Ermoupolis. Especially in Piraeus and the area of Kastella, a whole neighborhood bearing his name still survives. It was in such a neoclassical house that Giannis Tsarouchis was born in Piraeus, and in another similar one that he grew up, while the eclectic buildings of Ziller in front of Alexandra’s Square, which overlooked the Saronic Gulf, were painted with religious sensitivity throughout his career. Famous are also his depictions of the Neón, Mavrokefalos, and Pantheon cafés, where he combined the magical rendering of Athenian light with the precision of the Doric proportions of the houses, which the Hellenized architect drew from both classical antiquity, Pompeian villas, and Palladian Renaissance. From this entire dreamlike world, which demonstrated the dynamism that reborn Greece had acquired in the transition from the 19th to the 20th century, today almost nothing remains.

Not even beautiful ruins. Since loss has replaced beauty, and the neo-barbaric, unequal, and aggressive reconstruction—the aesthetics of contractors, the dictatorship of profit—has ostracized measure and the imposing charm of true architecture. Since then, loss will be the cost of every necessary (?), so-called development, so that Athens ultimately becomes the city of non-architecture. Of amnesia, of decapitatio memoriae.

Tassos Vrettos

This unique recording of loss is undertaken in this exhibition by the multi-dimensional photographer Tasos Vrettos, who insists on revealing fragments of beauty even in the chaos of the monstrous city or in the escape through staging other ways and other times. As happens with the foustanella-wearers in the old café or the Evzones parading in impeccable formations in the city center. Since only fragments or fleeting images, like those Vrettos captures while driving in the famous Omonoia Square circle, can offer a sense of the charming past. With the Bageion or the Alexandrion—both works of Ziller—gaping as uncomfortable ruins of our indifference. Personally, his photographs remind me of the black-and-white cinema of Nikos Koundouros, of Days of ’36, of Theo Angelopoulos’ The Travelling Players, and Lakis Papastathis’ Chronicle of the Greeks.

Yannis Tsarouchis, Cafeteria The Parthenon, 1955

Opening: Thursday, 31.10.2024 (19.00)

Duration: 31.10 – 29.11.2024

Free Entrance

Leave A Comment