An original music-theatre performance on Euripides’ Hecuba, directed and performed by Konstantinos Hatzis with music by Giorgos Koumentakis, is presented from 19 to 23 March at the National Glyptotheque.

An original music-theatre performance on Euripides’ Hecuba, directed and performed by Konstantinos Hatzis with music by Giorgos Koumentakis, is presented from 19 to 23 March at the National Glyptotheque.

The history of man, his perpetual thirst for power, destruction and war, as a heartbreaking portrait of the modern world, using Euripides’ words and the face of Hecuba as a vehicle. A study on war, refugee, genocide, hope, dream, nightmare and darkness.

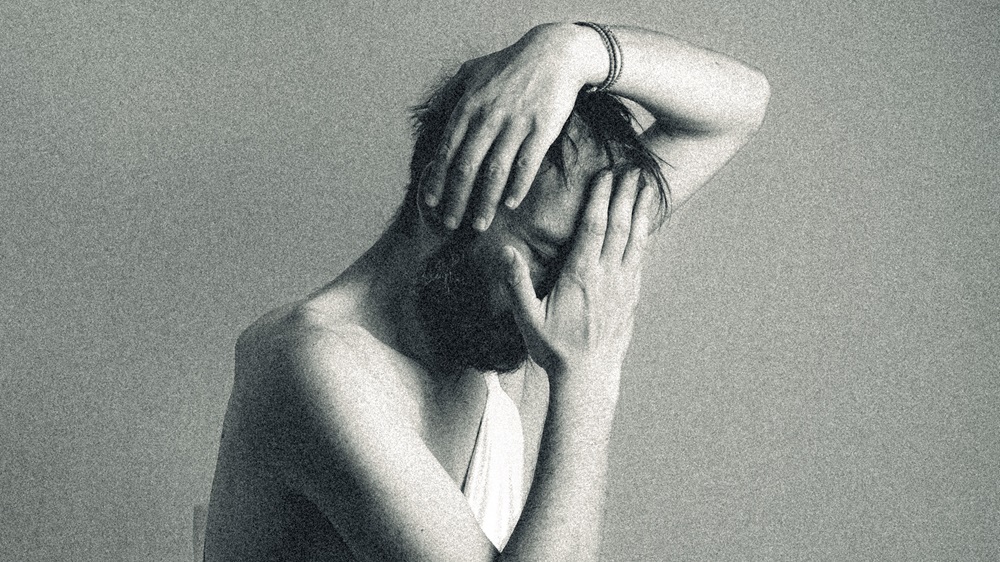

The face. The mother. The earth. The homeland. The Queen. Hecuba through the world of the dead crosses time like a curved arrow. She wanders among the ruins, the dead bodies, the mud, the blood. Her old body lying on the “hard, scorched earth” converses with gods and men. She struggles, resists, rises up and stares into the terrible face of war. Her word echoes deafeningly through the centuries over and over again. Music follows the same path. Another” wandering. Human steps. The rhythm sometimes fast, sometimes slow, steady or irregular, certain or uncertain tells the story of each person wandering in an empty, ruined city. Quick breaths, rattles, fragmented whispers.

It is a stitching and not an adaptation of Euripides’ well-known tragedy, as the tragic poet’s speech will be heard in its entirety in dialogue with the music and some songs by Giorgos Koumentakis in conversation with the National Glyptotheque. The performance Euripides’ Hecuba draws its inspiration from the works in the Glyptotheque. The story of the tormented Ηecuba who is transfigured into a maenad uprooted from her native forest, preparing to be buried forever in the soil of a foreign land, other than that of the hedonistic adrenaline-filled eschaton she knows, which she rules as queen of the land, converses heartbreakingly with the past of Hellenism everywhere, against the background of the greatest sculptural creations of the last centuries. The National Glyptotheque hosts, among others, Penelope (1873) by Leonidas Drosis, Hippocentaurus (1901) by Thomas Thomopoulos, Lot’s Wife (1962) by Froso Efthymiadis-Menegakis, the Head of Alexander the Great (1958-1993) by Dimitri Kalamaras, The Trojan Horse (1970) by Ioannis Avramidis, The Centaur (1985) by Sophia Vari, etc.

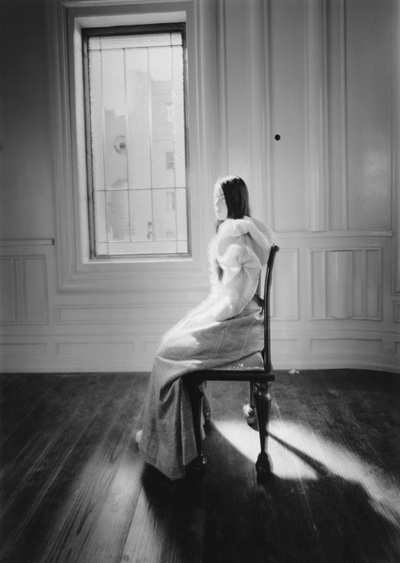

Hatzis’ Hecuba, here, functions as the alter ego of Dimitris Armakolas’ Anadymomeni (1975) as a work-symbol of Greek society, of the mother who emerges from her (all-)own abyss to share her drama, to redeem herself through the catharsis that she herself claims for her own micro-pouch, to leave her indelible mark on the construction of the social macro-history of Greek life. The mark of her family’s memory. Memory is considered a decisive factor in the formation of the cultural identity of a community or a nation. It is linked to the understanding of the past, the collective experience and the values inherited from previous generations. The sculptures bear witness to every passage, every monumental record and in this performance, Hatzis’ Hecuba is transformed into another moving-air sculpture seeking its way back to the Troy showcase, where it rightfully belongs.

Leave A Comment