The solo exhibition “I want to be the Hero of my story” by Artemis Potamianou at ENIA Gallery is extended until 29 June 2024.

The solo exhibition “I want to be the Hero of my story” is the second part of a trilogy of exhibitions. The great interest from the public and the presentation of the artist’s solo exhibition and the first part of the trilogy entitled “Your history, it’s not my story” at the Municipal Gallery of Larissa – G.I. Katsigra Museum (curated by Efi Michalarou), led ENIA Gallery to extend the exhibition.

The exhibition presents five in situ installations composing a multi-layered narrative on the female condition, a continuation of the problematic of her previous solo exhibition “Your history, it’s not my story”.

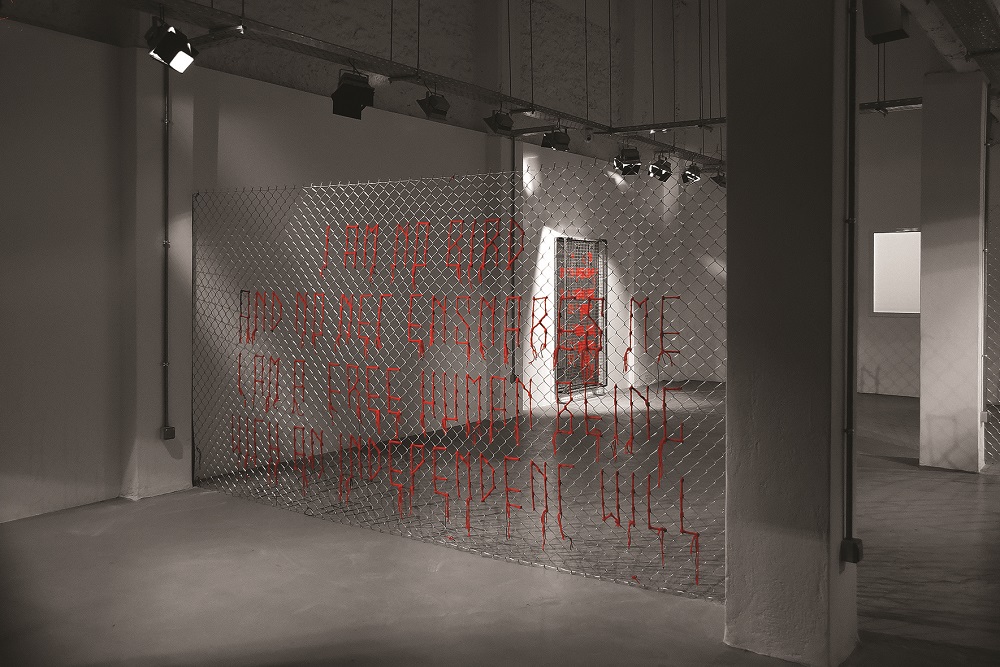

The exhibition is introduced with Which side you are on? fences, a tribute to Emily Dickinson. The installation’s wire mesh, which in itself evokes strong associations, leaves little choice for the viewer by defining a predetermined path through the space. The shadows of the barbed wire on the walls and floor together with the red embroidered texts give a labyrinthine dimension, accentuating disorientation in a space that is empty in front of and behind the barbed wire. The fence guides the viewer to the exhibition’s only access route, setting boundaries, as is the role of any good fence. After all, “good fences make good neighbours”.

The story of the poet Emily Dickinson is well known: her “open” poems were censored during their editing by editors and translators. She is one of the many cases of women writers (like Charlotte Brontë, a quote from whom is also used in the play) who first claimed the opportunity to have their voices heard and then to maintain the authenticity of that voice, without translation and interpretation, in order to be judged and to take their rightful place among their male colleagues.

Potamianou utilizes lyrics from Dickinson’s poems to return to the dialectic of managing fears, claiming identity, the loneliness of visual creation-and its questioning.

The barbed wire refers to property, a boundary but also a restriction, an obstacle to free passage. But it is perforated. Ideas, creativity are difficult to harness, as the examples of Brontë and Dickinson show.

Potamianou’s gaze is visual. The literary analysis of the poems is not the point of her research. Dickinson’s work is used first for its value as an experiential experience by the visual artist and then as a mechanism for visual self-awareness.

A path away from authority is laid tile by tile in the next work, Silent Revolt, a series of building materials/portraits where personal objects are cemented, articulating a set of alternative narratives of stories of silent everyday life, a pattern of traces of women-real women-who lived in the past or live among us, claiming their space and their role in the fabric of things. Here, the grid is internal to the cement, an element that holds the structure together and makes it as solid as these women. The voice of the silent women is there, as long as one has ears to hear it, or eyes to “read” it. Potamianou’s concrete portraits give equal space to each woman-the equality they lack in everyday life-unashamedly presenting objects of fashion and beauty next to beloved works of art, tools of labor, and utilitarian objects that accompany them, highlighting their similarities and differences.

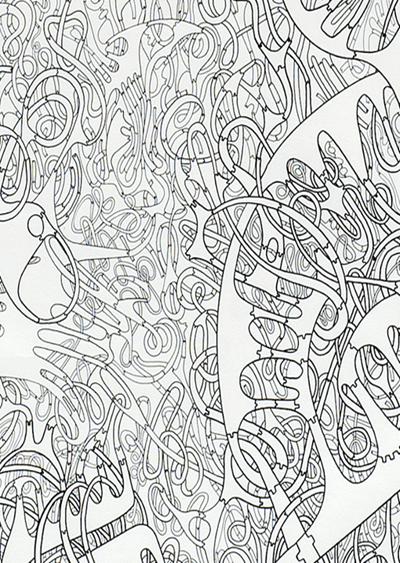

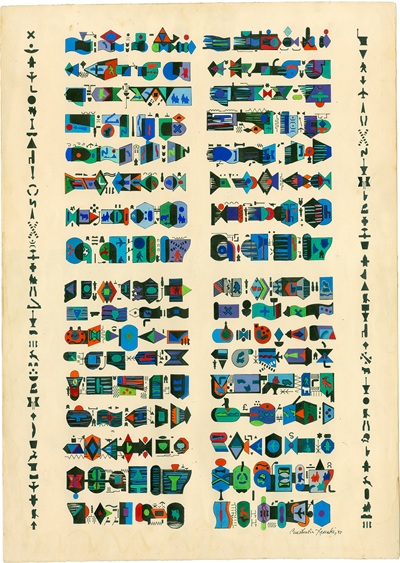

Potamianou uses a different case of female voice and creativity as a starting point for May’s work. The child of two talented parents, William Morris and Jane Morris, May Morris’ work was overshadowed by that of her parents. Potamianou begins by trapping May in her family name and returns with references to the wooden cages of her previous exhibition. Here the cage is transformed into a wooden structure-an additional grid-which, like the Morris family, provides support for the works to make their exhibition possible. Artemis works with successive abstractions of May Morris’s “Seasons” embroidery. The colourful rosewood with parrots ready to fly now traced and black and white along with the ever-present pattern of barbed wire mesh makes up the background behind the Mondrian canvas on which Potamianou this time places her manuscript pieces. The choice of medium is not accidental. Like society, especially in the case of women, watercolour is unforgiving. Some mistakes are corrected, but not covered, and the paper’s tolerance is short. In May the birds-symbols of female fragility-are trapped. Watercolor gives them substance but also captures them on the wire-mesh canvas, as Morris herself had previously embroidered them on her wallpapers to adorn the walls, to decorate without ever achieving freedom.

The stories of creation within confinement, real or that of obscurity and social restrictions continue in The Supper. The collage of the female creators in the work with sandbags and the iron frame/scaffolding that holds them at a distance bring to mind works of fortification in museums during World War II and ways of enclosing artworks for transport. (Depending on the mood of the viewer, they also recall the enclosure of Antigone in Sophocles’ tragedy of the same name, especially if we focus on the mechanisms of exclusion in art history.)

The title has references to the Last Supper and Plato’s Symposium.

I wonder what these twelve women painters, depicted in their mostly self-portraits working or painting, are discussing as proof of their existence and action? What is certain is that despite their lonely path, they are not alone. In a visual argument that argues that creation is not ultimately a solitary process, Potamianou composes in Supper a different mosaic of women, a Chorus who, alongside the unfolding work, share their stories-the building blocks for the path of others after them. Their example is here and asserts its place by articulating a political discourse and creating narratives that are relevant to every person who has experienced the power of another person, institution or social environment over them.

Lastly, the exhibition closes with a game of perception and memory. Gilt Cage with direct references to the iconic Mary Wollstonecraft originally is just that: a piece of house cut off from its wholeness, enclosed in a cage.

On the outside of the cage an empty chair, similar to the one inside, invites the viewer to sit down. At first glance, the covered furniture brings to mind loss, preparation for a long absence, or abandonment. Inside the cage, time stands still, the season does not count. The first reading of loss is shaken by the gloves and objects left on the covered furniture-the evidence of life afterwards. But after what? Who do they belong to? Do they belong to Nora from Ibsen’s Α Doll’s House who escaped from her cage? The interpretations are open, many, possibly personal, but the feminist reading of the play is clear: The woman inside the cage has escaped. The man who was watching her from the outside no longer exists. Gilt Cage marks an end of an era.

The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue with texts by Guerrilla Girls, Faye Tzanetoulakou, Delia Potamianou.

Entrance to the exhibition is free to the public.

Εxhibition Opening: Friday 20 October 2023, at 19:00

Duration of the exhibtiion: 20 October 2023 till 29 June 2024

Opening Hours: Thursday– Friday 12:00 – 20:00, Saturday 12:00 – 16:00

Mesolongiou 55, Zip Code: 185 45, Piraeus, Τ. (+30) 2104619700

Leave A Comment