Seekers of the rare gems of the Greek theatre scene agree that Caesarios Dapontes’s “The Sacrifice of Jephthah“, presented by director Iossif Vivilakis and the “Othonion” group for the first time in Greece at the Kalirrois Theatre, is one of the experiences of the season that one ought to offer oneself. Walter Puchner wrote about the performance that “it is another bold project of resistance to this cultural mash that overwhelms us“.

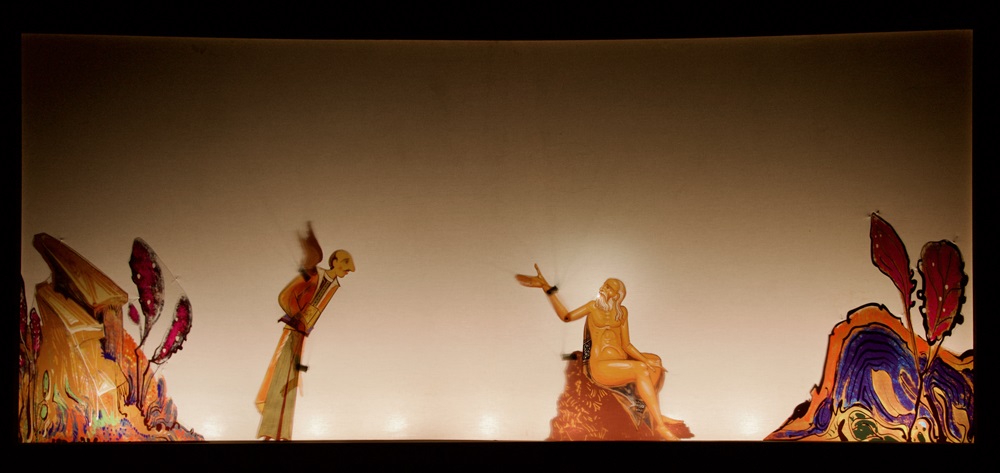

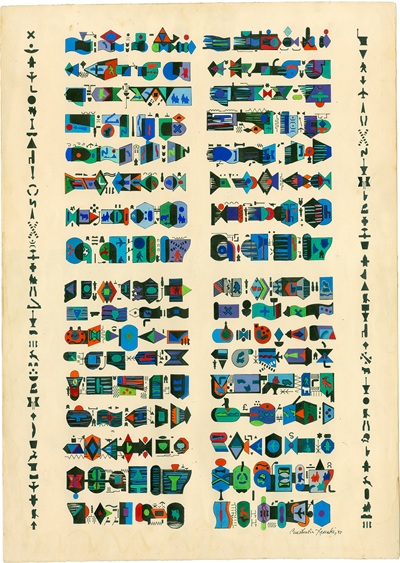

Indeed, the group ” Othonion”, created by Iossif Vivilakis in the context of a course on shadow theatre that he taught at the Department of Theatre Studies of the University of Athens, returns with a multifaceted performance that highlights the influences of Dapontes from ancient Greek theatre and folk tradition. At the same time, the musicians on stage, the ethereal presence of the soprano Gina Foteinopoulou in the role of the daughter, Athos Danellis‘ team behind the curtain of the shadow theatre, the painted sets and an almost Byzantine approach to the figures by Yorgos Kordis create a sublime atmosphere to which one mentally returns for days after the end of the performance attended.

On the occasion of his group’s performances, director Iossif Vivilakis shares with Days of Art in Greece his knowledge of Dapontes’s work and the directorial approach he followed in bringing together artists from different fields of action.

Katerina Michalaki, Athos Danellis, Nikolas Tzivelekis

Dapontes’s work, especially with the sacrifice of the only daughter, echoes the sacrifice of Iphigenia. Tell us about how Dapontes’s work is connected to ancient tragedy.

The “Sacrifice of Jephthah” refers to ancient tragedy because it assimilates structural elements of ancient drama. The text itself as a composition has a dramatic form with an extremely lively dialogue, but also stage directions, which means that the author of the play, Caesarios Dapontes (1713-1784), imagined his drama to be performed in a separate space, in a stage setting. The Prologue notes that the plot is described “tragically, but does not keep the rules of tragedy unbroken”. Clearly the poet is familiar with the ancient standards because of his deep and extensive education and would have been exposed to Euripides’ Iphigenia.

What is extremely interesting is that the play begins in the prison where Dapontes himself is imprisoned in Constantinople and ends with a monologue and a wish to Jephthah and his daughter to accept the tragedy he composed as a hymn and praise in order to intercede to Christ to end his personal adventure. Another element is Dapontes’s reference to not following the rules for writing a tragedy, although he follows Aristotle in terms of the tragic protagonist: a person with special abilities, a military leader, a war hero, who experiences a story and is led to destruction because of a failure.

A strong element in the work that brings it close to the logic of ancient tragedy is the Chorus and the chorale chants in the third act. The main Chorus is the group of girls accompanying the daughter to the mountain to mourn her. The Chorus sings and moves around the stage participating in a series of dirges expressing emotions so that the audience can experience and penetrate the psychology of the heroes and the poet’s views. To this dance are added groups of Sirens, Charites and Nymphs. Through the presence of these otherworldly creatures, presented as the daughter’s relatives, we have the opportunity to see the story from the women’s point of view and think about how they view a male warrior who has made a terrible mistake.

The lamentation in the performance functions as catharsis and I mean that the reception of the horrible experience is done in such a way that the viewer is not hurt, even though the distant daughter becomes extremely familiar and recognizable. The ceremony with the dirges is conducted far from culture, out of time, thus acquiring a universal dimension that brings it close to the tradition of the folk song.

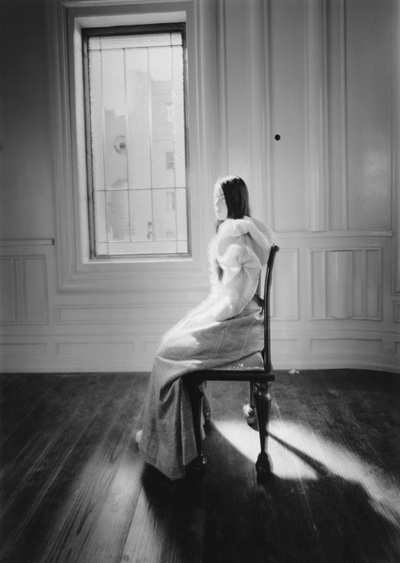

Gina Foteinopoulou

Your performance is very diverse. It combines music, acting and shadow puppetry. What is your directorial role in terms of bringing together all these different art forms?

When people ask me which category the performance belongs to, the answer is difficult because the scenic effect escapes conventional categorization. Dapontes’s text, which is a masterpiece, has occupied my research for over fifteen years and led me to make specific choices for the performance, keeping in mind the basic question of how to render the ritualistic element that would lead to the audience’s participation.

I was thinking that everything in the show should contribute to a process of separation and reconciliation with death and the presence of the Chorus gave the idea that the whole show should have an operatic dimension. The starting point, of course, was to get the dramatic text right, the poetic speech of Dapontes, which is written mainly in fifteen-syllable rhymed verses, but also to show on stage the whole story up to the sacrifice, which is historically placed around 1106 B.C., in the time of the Judges of the Old Testament.

I edited the text dramaturgically in order to have a body that would serve the performance, a dramatic story that would be understandable to everyone, that concerns us today and that we have to tell with images and music. I chose the pieces that would be the songs of the heroes, without resorting to adaptation, except in some places where I added lyrics that promoted the action.

The imagery for the daughter is rich, as is the material of the work in general, which has a variety of origins, elements that we wanted to show in a simple and natural way. Therefore, the aim was not to have a typical theatre performance but to experiment in a variety of forms, with shadow, three-dimensional body and musical forms in a limited space, such as the Kallirois Theatre, a blackbox, which suited us functionally. Shadow theatre was deemed necessary because at the time of writing it was a favourite artistic genre in the Ottoman Empire, while at the same time creating a sense of distance, particularly in the violent scene of sacrifice.

Karagiozis as a connecting link appears in the role of the Poet, who was retained at the critical points of the story, holding the role of the narrator, and relieves the atmosphere when the tension reaches a borderline state.

The highly aesthetic coloured figures and the scenery created by the great painter Yorgos Kordis gave us the visual atmosphere we needed. The characters behind the curtain are animated by two excellent players, the master builder Athos Danellis and Nikolas Tzivelekis, one of the most important representatives of young shadow theatre players. There is a crystallization in simple lines of the art of acting in shadow theatre, Fotos Politis has said, and this is what we try to conquer in all the performances with our group Othonion: simplicity and sincerity. In each of our stage attempts this is submitted to the judgment of the audience. The players do all the roles through the alteration of their voices and enter into the process of acting, as is the case with all actors.

From then on, it was obvious to me that music should be written, which will be performed on stage and will aesthetically seal the performance. Theologos Papanikolaou undertook the part of the composition and the interpretation together with the amazing musician Giorgos Tamiolakis on cello. Papanikolaou created an original sublime musical composition that works throughout the performance and moves between Byzantine music, the folk tradition of the Mediterranean, combining also forms from European music.

The big challenge was to have with us a performer whose body would be an expressive medium in front of the curtain. The lyric singer Gina Foteinopoulou was the ideal choice, because she combines vast experience in opera and acting and contributed decisively to the look of the performance. She took on the role of the daughter, but also all the choral parts which she performed with excellent mimicry, movement and gestures in front of the bard. Essentially in the daughter’s mourn, with Fotinopoulou we have the climax of the tragedy as expressed by her friends on the mountain. Katerina Michalaki also contributes to the song in the role of the mother who performs it behind the curtain, while helping the players.

The assembly of the individual elements was not an easy task since we had to serve the performance as a whole and move along roads and soundscapes between East and West. Furthermore, we had to combine two different ways of acting, behind and in front of the curtain, for Foteinopoulou to converse with the players, and this was not only a matter of coordination, but also of familiarizing different artistic disciplines. An important point is that not using microphones worked liberatingly for the interpretation of all the performers. A balance still had to be found between the various expressive means in order for them to work together harmoniously on stage, as well as the rhythm of the performance. A lot of individual and collective work was required to reach the final result, the realization of the stage event, in order to bring out both the freshness of the text and the power of the story to touch the audience, something that is unpredictable and different, due to its uniqueness, every time.

I feel lucky to be working with this group of multi-talented artists who have a high sense of co-creation and this was evident throughout the rehearsal process up to the start of the performances. They care about each other’s work and I say this because it is not a given that the performers will connect in a show. It’s not enough to do your job well on stage, it takes more than that when you’re part of a team: paying attention to what’s going on at all times and giving space to your collaborators so there’s constant stage communication. We are constantly learning new things from each other. What we’ve been able to discover in this collaboration we’ve been able to do because we’re together and we trust each other.

Theologos Papanikolaou

Your approach to Dapontes’s work seems to be quite inspired by the element of folk tradition that one finds in the laments and the supporting characters. What can the representation of folk wisdom and aesthetics teach us today?

Interestingly, the chorus members in the play do not express the values of the city but the collective experience of vulnerable females. Nature serves as the safest context for them to express themselves, share their traumas, show their beauty without fear of the aggressive eyes of men because they “lack the cunning eye of man” and the “envious, curious and medicated eye” of the women of the city, as Dapontes says.

In the wilderness and in nature the conditions change and a new community is created with the sisters of the heroine, here the daughter can express herself freely, whereas in her natural family she was limited only to obedience in order to fulfil her father’s vow.

The lamentations of the play are based on materials of folk tradition, on rituals and practices that are lost in time but that we know from the choruses of ancient tragedy, where the pain of the body is represented in order to release all the burdens that overwhelm the daughter’s friends. Before the lamentation begins, there is a difficulty in expressing grief, which we know from ancient drama and Byzantine literature, as well as in ecclesiastical preaching. There is an awkwardness until reconciliation with the fact of loss. Here, we have a series of songs but also a whole ceremony with strong elements of violence, such as wounding the body to the point of bludgeoning, beating the chest and beating the head. The maids of the daughter after untying their hair are transformed into wailers who go into a frenzy. They say at one point:

“Let our face be marred, let our cheeks be torn

And let all face and cheeks be bleeding.”

The performance of pain reminds us of Aeschylus’ “The Libation Bearers”, where in the procession of the women the lamentation requires facial mutilation. As alien as these practices may seem to our time, here we enter the process of thinking about our need to mourn, that is, to express our grief for a lost person rather than to push our feelings away under cloaks of propriety. The play, ultimately, carries over laments from funeral rites and shows us what it means to be compassionate. Mourning is the business of the group, of the community. On the other hand, we see how effortlessly the ancient world with its out-of-this-world female forces is integrated into the post-Byzantine environment. Using the Bible and the story of the Old Testament as a starting point, traditions are ingeniously combined in a bold and highly creative way. Dapontes preserves records of popular culture, oral narratives, songs and practices that affirm the importance of tragedy in human life.

Giorgos Tamiolakis

You have taught for many years at the Department of Theatre Studies at the University of Athens. How does the educational process differ from the practical application of the elements of directing and theatre studies during the preparation of a performance?

Theory and practice are interconnected realities. The performance cannot be understood without theoretical elaboration, historical background and knowledge of the circumstances of the text’s writing. The introduction of theatre studies at university level has drastically changed the map in the theatre field and anyone who enters the research process is immediately aware of the close relationship between practice and theory. In my consciousness the pedagogical element links education and performance preparation. It requires preparation and analysis both in the classroom and in a group of performers. Both come to learn, to discover, to go further, to move. The difference is this: when the lesson is theoretical or historical, the experiential element in the learning experience is limited. This is removed in laboratory courses where creativity soars and everything becomes unique. Here’s why theatre arts should be more active in schools and not on the sidelines, as is currently the case with theatre education in a few primary school classes. In preparing a performance from the first reading, the group soon moves on to practice, i.e. creating the roles, learning the songs, building the sets and costumes. However, in both cases, what Pirandello has said about the art of theatre applies: “It is an act of life created, minute by minute, on the stage.” Whether it is a stage or a classroom, what happens there is an act of life.

***We would like to thank the director Iossif Vivilakis for the permission to use the photos he took for the needs of his performance.

Leave A Comment