To a greater or lesser extent, through school celebrations and commemorative events, the enthusiasm with which the Greeks enlisted in the army at the outbreak of the Greco-Italian War, the successes of the army, and the advance on the front are well known. However, the distance from the events, the study of history through books, and the reproduction of public history through official anniversary speeches leave out the citizens who continued to live in cities and villages.

The pages of the daily press reveal how people’s lives changed with the outbreak of war. Focusing on the first week of the war through the pages of the newspaper AKROPOLIS, the adaptation of the daily life of the capital’s inhabitants to the new reality is highlighted. The fear, anxiety, and excitement that gripped the Athenians from October 28, 1940, can be found in the pages of the newspaper, in the headlines with the big titles, but also in the small articles on the back pages, in the classifieds, and in the advertisements.

The Greeks were certainly expecting war. Italian preparations in Albania were obvious, while the sinking of the destroyer Ellis left no room for complacency. The Hellenic Army General Staff had already begun the necessary preparations to counter an Italian attack, but the official position of the state remained one of neutrality. This also seems to have been the line taken by the press. Of course, developments on the war fronts in Europe and Asia were covered in detail. However, the newspaper limited itself to reporting on the conflicts without showing favor to either side.

Despite the dramatic international developments, in Athens, just a few days before the war, activities continued that seemed rather out of place given the climate. Perhaps the most characteristic example was the “Successful Greek Fashion Show” on October 18. In fact, the internationally renowned Vogue magazine devoted pages to the event, as the newspaper informs its readers.

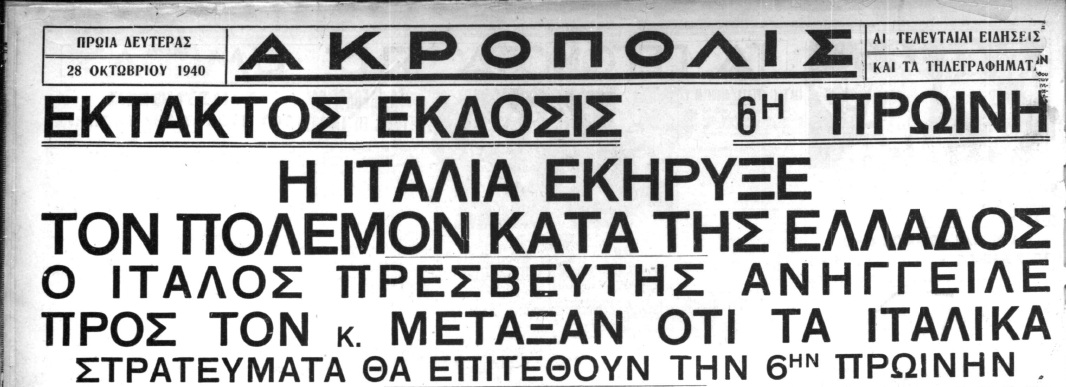

Even one day before the declaration of war, there was no indication that the country would participate in the war. However, this would change with the ultimatum issued by Emanuele Grazzi. As is well known, the Italian ambassador delivered the ultimatum to Metaxas at 3:30 a.m., and the time of invasion was set for 6:00 a.m. The newspaper AKROPOLIS published two issues on October 28, the first of which had obviously been printed the day before. The front page emphasized Greece’s “disposition” to remain neutral in the war and denied reports of an incident on the Greek-Albanian border. However, in a special edition, the newspaper reported on the declaration of war: “Italy has declared war on Greece…”

In the days that followed, developments on the front, mobilization, the defense of the Greek army, and the counterattack dominated the newspaper’s front pages. Alongside these, articles reported on international support for Greece and military aid to the country, mainly from England.

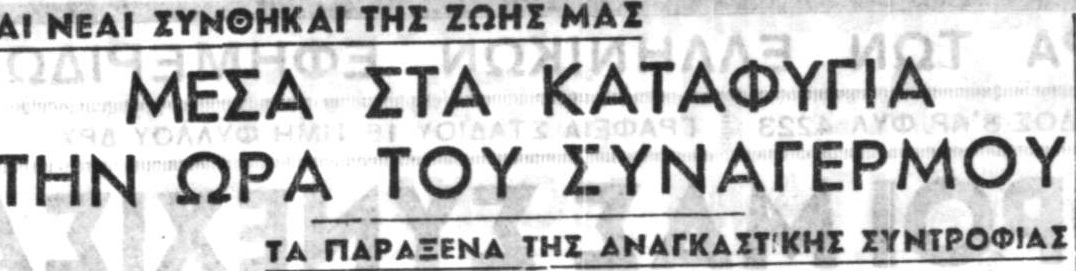

However, practical instructions are also provided on how to deal with possible bombings, alarms, and living in shelters. Shop opening hours are set, and recommendations are made to avoid using electric lighting, both for economic reasons and for air raid protection.

As early as the mid-1930s, it was mandatory by law for new buildings to have shelters that met specific strict specifications. The Spanish Civil War and advances in military technology had made it clear that aerial bombardment would be the main threat to civilians in an upcoming war. As a result, there were hundreds of shelters in businesses, public spaces, and private residences in Athens. The authorities urged residents to take refuge in them in case of an alarm or at least in nearby basements, while obliging company owners who had shelters to allow free access to them throughout the day.

Nevertheless, there were quite a few Athenians who, upon hearing the siren, not only did not run to the nearest shelter, but stood in open spaces, even at windows, rooftops, and courtyards, searching the horizon for planes. However, the majority of residents gathered in the shelters. During the few hours they had to remain there, chatting with those around them, even if they were strangers, the children played with the toys they had brought with them, those who could afford it treated those around them, and everyone waited patiently for the danger to pass. As for the behavior of the Athenians in the shelters, the author emphasizes the politeness with which everyone behaved, while also noting the phenomenon of some people taking the initiative to guide others.

Indicative of the new reality is the “practical advice” of a reader, a public works contractor, published in the newspaper: The reader advises that there should be one or two pickaxes in the basements so that, in case the building is destroyed by bombing, those trapped inside can open a way out. Equally characteristic of the conditions is the small advertisement of November 3 for “anti-aircraft waxed fabrics for complete blackout of your windows…”

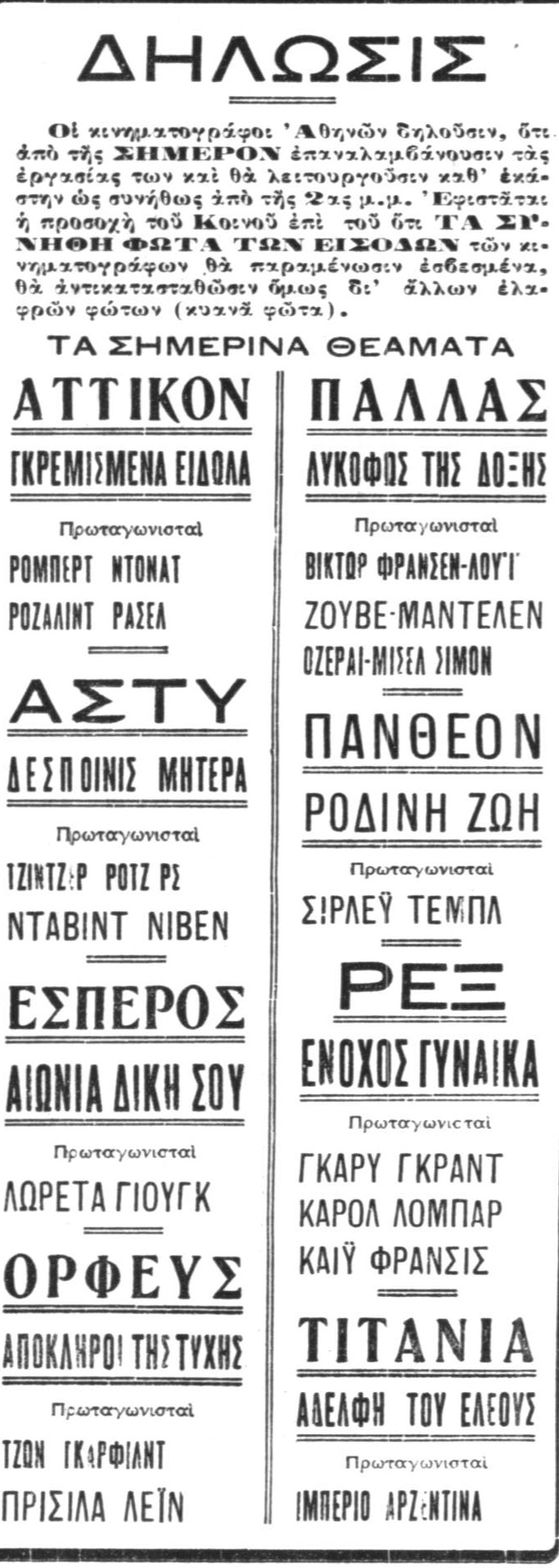

The first measures taken were to restrict public transport services following the directive from the Deputy Ministry of Public Security to turn off the lights in railway stations, trams, cars, as well as homes and hotels. However, despite the fear of bombing, social life in Athens continued, albeit under new conditions. On October 30, the cinemas of Athens, Attikon (The Citadel), Pallas (The Last Command), Asty (Ms. Miniver), Pantheon (Rosy Life), Rex (In Name Only), Esperos (Eternally Yours), Orpheus (Dust Be my Destiny), Titania (Sister of Mercy), in a joint statement, announce that they will “operate as usual” but the entrance lights will remain off and will be replaced by soft “blue” lighting.

The theatres, after a brief interruption, resumed their performances, albeit only in the afternoons. In the following months, revue performances were staged in many of the Athenian theatres with the aim of cheering up the Greeks and lifting their spirits. Following the example of the theaters, the Hellenic Conservatory announced that classes would continue as normal and would even accept new registrations. The exception was the Royal Theater, which refunded the pre-sold tickets for all its performances.

The pages of the newspaper AKROPOLIS, as well as other Athenian newspapers, reveal the efforts of residents to adapt their lives to the unprecedented conditions of war. And indeed, life in the city does not come to a standstill. On the contrary, life continues under new circumstances, with Athenians working, going about their business, and, of course, participating in the popular celebrations that take place after every victory on the front. Of course, this general picture, although true, is not the only reality. Each citizen individually worries about their relatives who are fighting, about the progress of the war, and about the safety of their children. In the end, the fear of aerial bombardment during the Greco-Italian War fortunately did not materialize, but from April 1941 onwards, a much more tragic fate awaited Athens…

Leave A Comment