In the first years of the 1960s in Greece, as in many parts of the world, the youth came to the fore, mainly through an organizationally strengthened student movement, having as its main demand the political and educational democratization but also the fair division of the produced wealth.

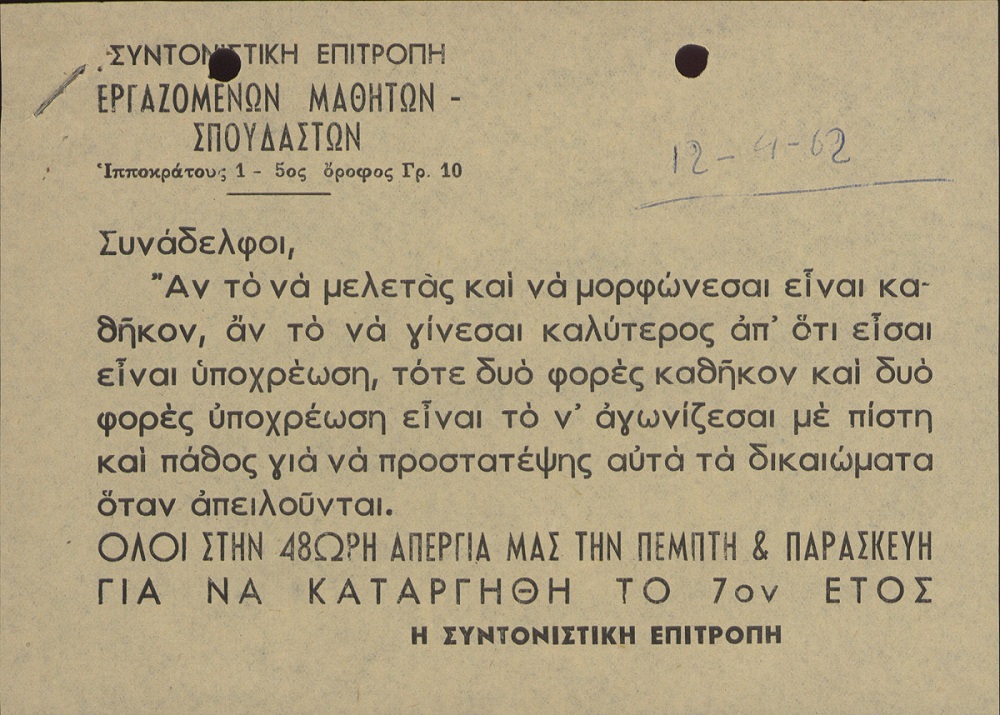

Then a special group of youth emerged, the working students, who worked during the day and attended the night high schools at night. The majority of them were young people aged 14 to 20, coming from the low social strata, children of poor families or who moved from the countryside to the cities to ease family expenses and to study working adult hours but for half or less pay. Their lives were dominated by long work, night lessons in a repulsive school environment, reading and little rest or entertainment. These harsh conditions often forced children to interrupt their studies.

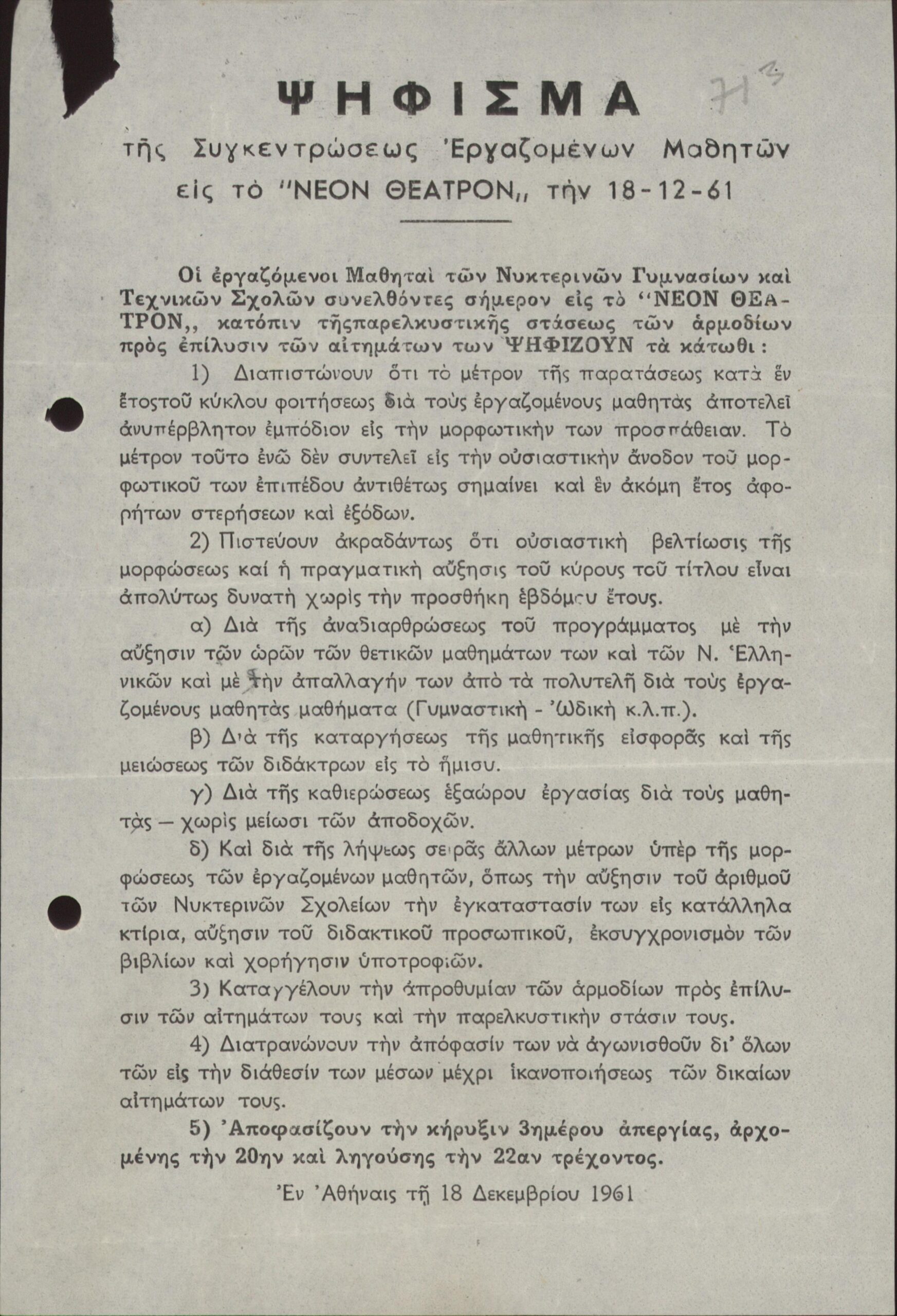

An economically and socio-politically emancipated group, the students of night high schools, were organized collectively as a special part of the student World, in early 1962 founding the Association of working Middle School students. The reason for the foundation of the association was the extension of their studies by one year (7 years). The foundation of the association was pioneered by builders and workers fighters of the left space, already organized in United Democratic Left, such as Christos Rekleitis. The participation in the association not only provided the working students with trade union protection but also the interaction of boys and girls with common references and interests resulting in the development of intense cultural activity with dances, excursions and guided tours to archaeological and other historical sites, musical afternoons, reading books and cinema. At the initiative of the Association, the branch newspaper Mathitiki (Student) was also published. Most of the children, who worked from the age of 8-10, experienced the uplift offered by dealing with arts and letters. Through the common cultural experience and the progressive political vision, feelings of friendship and solidarity, hopes for social improvement and decent living were cultivated, goals that are worth fighting for. Association Of Working Middle School Students aspired to feed society with young intellectually cultured and politically mature people, rallied around the wider progressive student movement.

The night students, through the permanent presence and intervention of the Association Of Working Middle School Students in the Panacademic Conferences, criticized the governance of the country and denounced the irresponsible treatment of issues of Education, Health, Labor. In addition to the abolition of the seventh year of attendance at night high schools, working students requested free education, more and better school facilities, free provision of textbooks, six-hour work, medical care, etc. Their demands corresponded to the expenses that the democratic government must provide to the student youth, who worked for the national wealth and the future of the homeland. The members of the association fought for the implementation of their demands with marches, abstentions and even hunger strikes. During the three years 1961-1963, the club was particularly militant. The working students and the Association of Working Middle School Students were accused and prosecuted under Circular 1010/1965 issued by George Papandreou as prime minister and Minister of Education, with the aim of dissolving the Lambrakis Democratic Youth. In contrast to the Association of Working Middle School Students, the Organization of Student Working Youth (ΟΣΕΝ) was active, a failed attempt by the authorities to break up the Unified Student Movement.

Despite the coordinated and persistent effort made, the working students failed to solve their basic problems, but the experience they gained, through the assertive process and collective action, contributed to the activation of the moral and social reaction and resistance presented by part of the youth during the dictatorship. The personal and collective vision of a more peaceful and just world kept the youthful flame alive.

The youth of the 1960s, proportionally, can be compared to today’s only in terms of the conditions of political decline and economic crisis where both were nurtured – but in different economic environments, with a common demand for a fair redistribution of wealth. The working students of ‘60s, convinced that progress, individual and collective, was in their hand, fought for it with all their might. Studies at that time were an asset and a guarantee of social and economic growth, which meant prospects for professional development capable of ensuring the decent survival of the middle-class family. Today the majority of young people, deprived of ideals and prospects, seek temporary enjoyment through ephemeral experiences, indifferent to the future. The subject is now individualized and therefore assertively weakened. Vocational rehabilitation is now in doubt for many young people equipped with degrees and specialized knowledge – that is, incomparably higher educations than their parents and grandparents.

The post-war economic development of the 1960s, social mobility and cultural liberation offered tο youth a vision and aspirations that pushed them to claim rights and freedoms, in contrast to the current reality that the dissolution of collective institutions, the eroded and powerless political institutions, the degraded value model and the way of life imposed by the ideology and practices of neoliberalism, have disoriented most young people from the vision of a more secure and just world. Collective frustration and social impasse have imposed inaction, resignation and nihilism.

E.Α. Desypri

Master of Modern and Contemporary Greek history.

Leave A Comment