Tzeni Klaudianou

Reading Room and Archival Research Department

General State Archives of Greece – Central Service

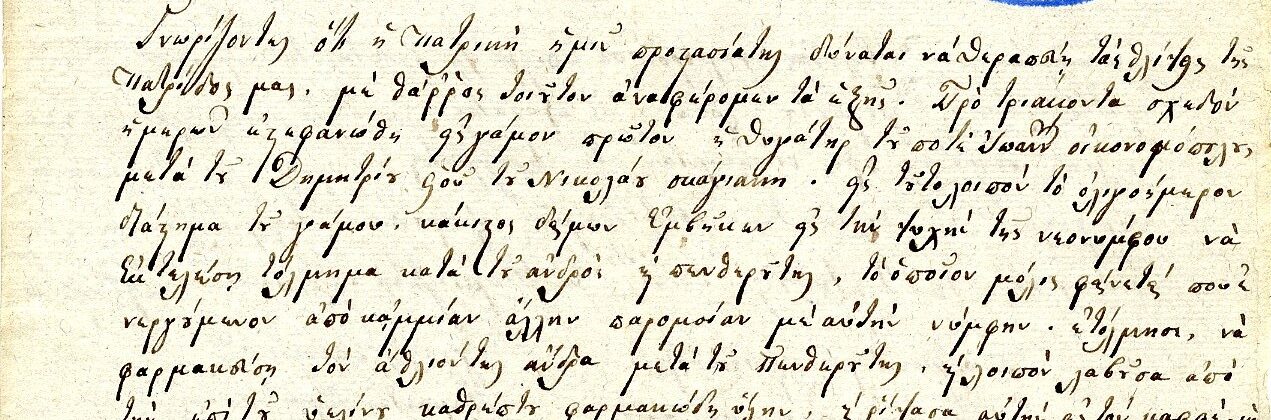

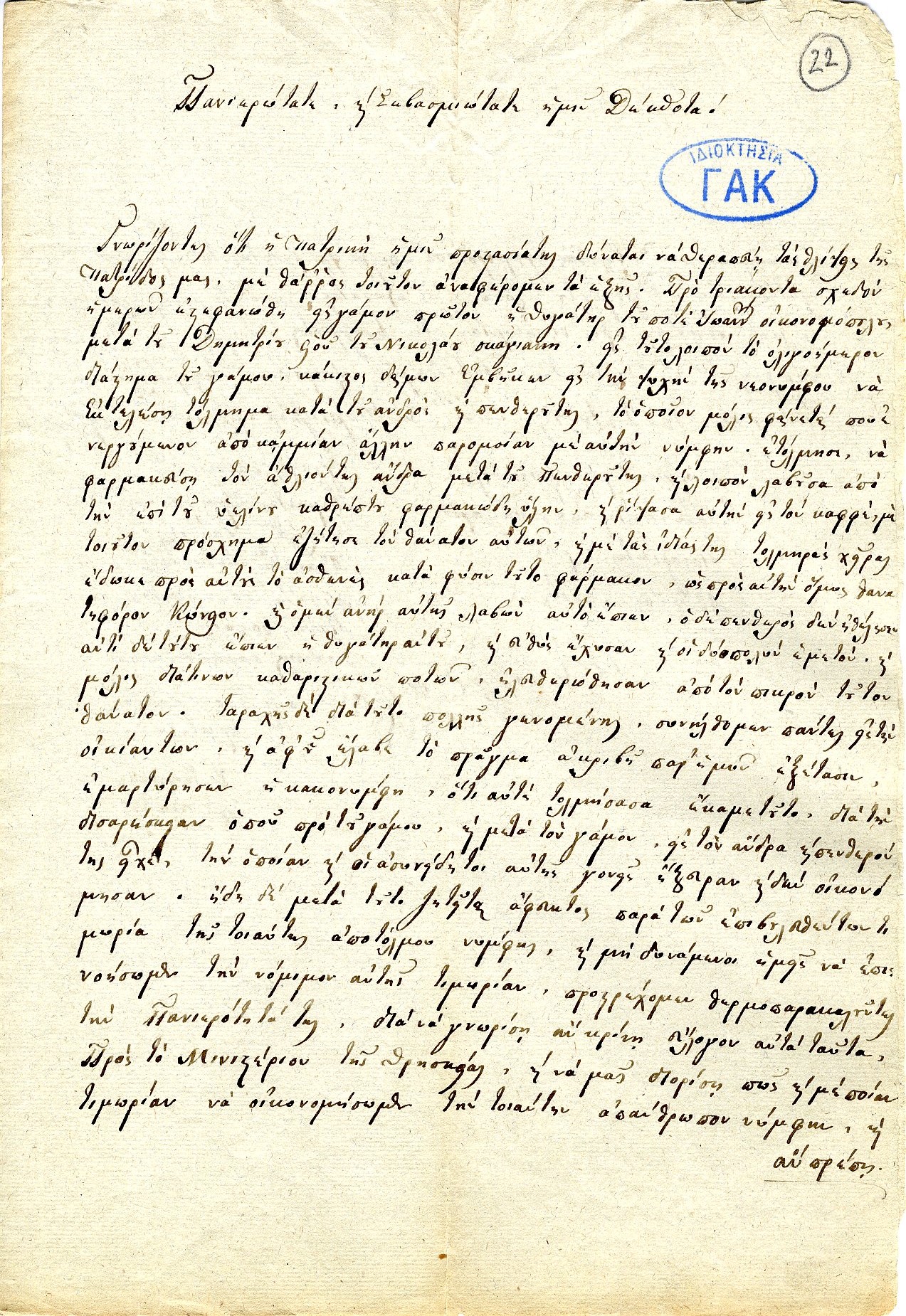

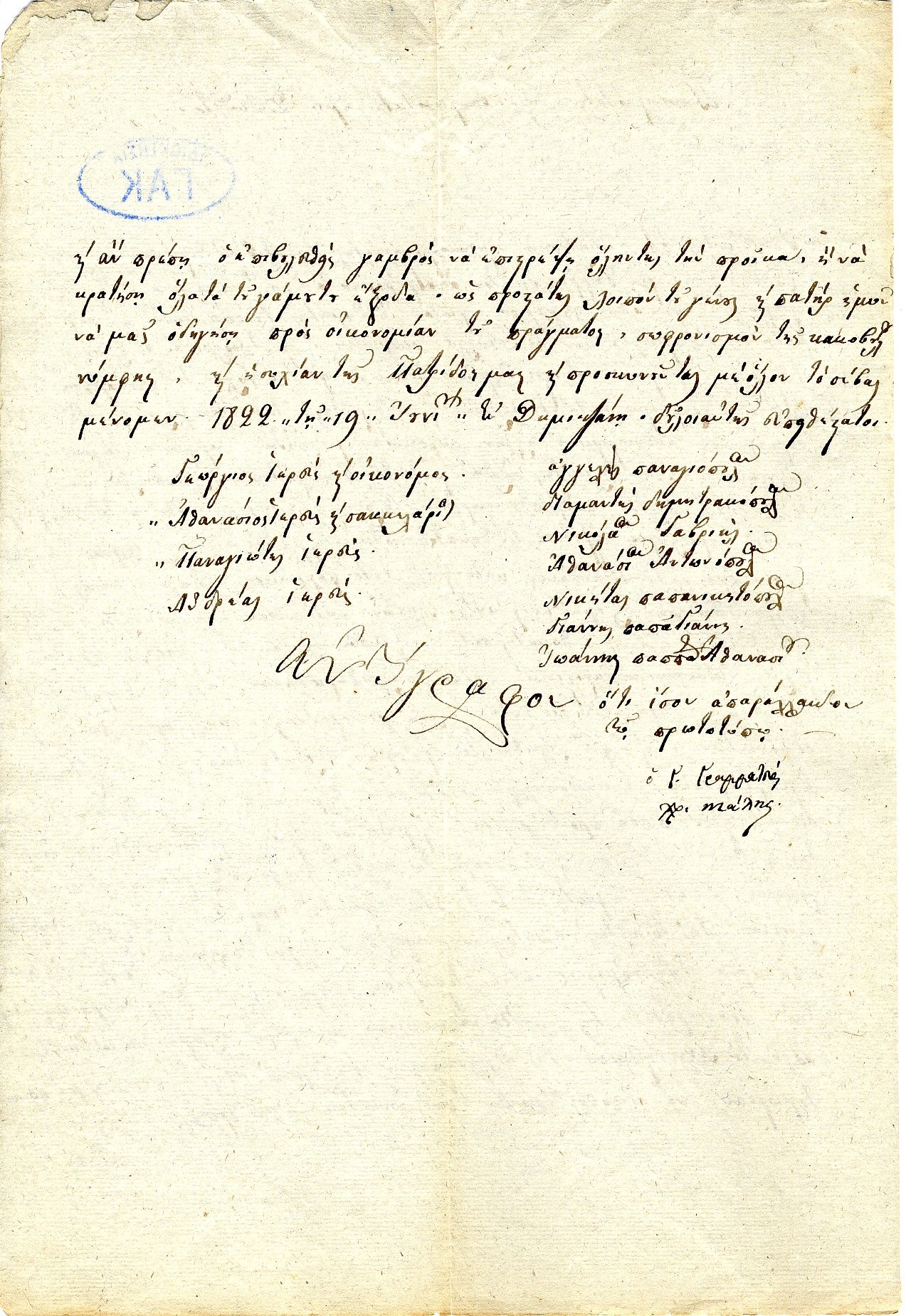

[Source: General State Archives of Greece – Central Service, Ministry of Religion and Education Archive (period of Struggle)]

Dimitsana, 19 June 1822. Notables and priests are asked to hurry to Nikolaos Skayannis’manor. Worried, they cross the narrow cobbled alleyways, go past the houses of Palaeon Patron Germanos and Oikonomou-Kazis, the secretary of Kolokotronis, and arrive puffing at the engraved wooden door between the stone posts. The revolution is seething in the Peloponnese, but the elders have no intention to confer about the sacred Struggle, or to evaluate the recent burning of the Turkish flagship off Chios by Kanaris and its possible impact on the provision of Dramalis’army who are heading menacingly towards the Morea.

Duty calls upon them to unravel a family tragedy: the persecutor is the young bride of the Skayannis family, who in their presence will confess to her hideous act. Ioannis Oikonomopoulos’ daughter, scarcely a month after her marriage to the young Dimitrios Skayannis, decides to poison husband and father-in-law.

One would expect that the “deadly hemlock” came from the powder-mills of the Spiliotopoulos brothers, who turned Dimitsana into a big “factory” preparing gunpowder. In truth, the thirst for the liberation of the fatherland prompted even women actively to participate in the mixing of carbon, nitrogen and sulphur. On the contrary, the “malevolent bride” smashed a mirror to pieces and emptied the “poisonous matter” into the coffee, which she herself offered to her unsuspecting victims.

The husband drank the coffee accepting the attentions of his young spouse with abundant joy. The father-in-law refused to drink and in this way the poisonous liquid landed up at Nikolaos Skayannis’ daughter and sister-in-law of the culprit. The drinking did not cause death but uncontrollable vomit. The administration of a purgative and the bride’s wrong impression that the mirror contained mercury instead of silver saved the two people.

What “most evil demon”, one wonders, drove the bride to such a daring act? What behaviour of the husband and the father-in-law caused her intense displeasure? Did her parents know the dark instincts of their daughter? The local dignitaries, having no experience of any similar incident, draw up a report to the Ministry of Religion asking it to indicate the punishment of the poisonous bride.

The dissolution of the marriage was inevitable; but the issue of the dowry would have to be settled. This is why the elders of the village wondered whether it ought to remain with the husband or be returned to the bride’s family. We do not know what punishment was inflicted on the perpetrator. Manuscripts of the same period mention the prohibition of a new marriage or the confinement to a monastery as penalties in similar cases.

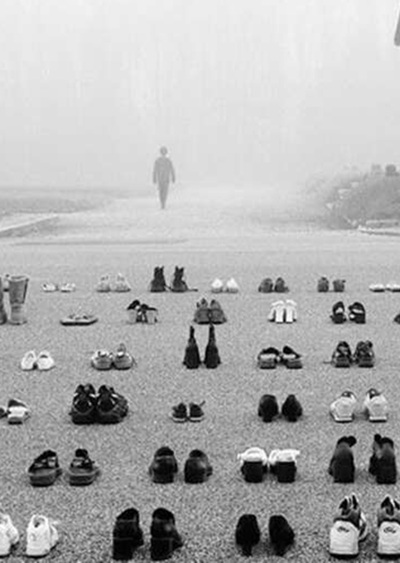

It is a document that refers to “another ‘21”. An unheroic, everyday ’21, but as human as passions are.

Leave A Comment