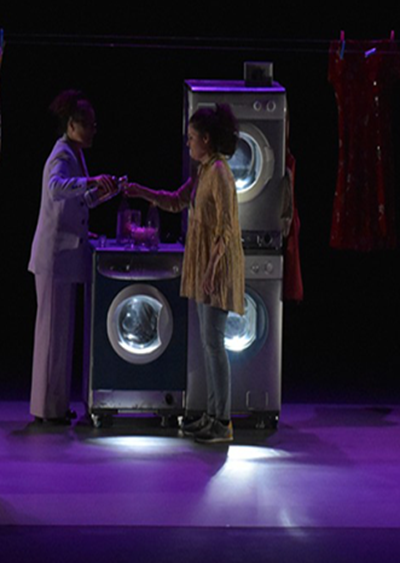

The performance of Aeschylus‘ “Oresteia“, directed by Theodoros Terzopoulos, thrilled the audience of the Ancient Theatre of Epidaurus, on Friday 12 and Saturday 13 July. Tickets for both days were sold out and people flocked in droves and almost reverently to the most important theatre of antiquity. The approach to “Oresteia” – the only surviving trilogy of ancient Greek drama – that the audience was about to watch differed greatly from the usual easy impressions of the school of deconstruction and unfolded before their astonished eyes the special way of working of Theodoros Terzopoulos, which aims at the emergence of the “Body” of the actor.

As the theatrologist-semiologist Maria Scicchitano explains in the programme that accompanies this production of the National Theatre Greece, regarding this special psychosomatic training of actors, “By activating the Body, the actor explores the material of the play and his role, opening unprecedented sonic, physical and energetic axes and thus releasing the special language that is inscribed in the Body of each actor“.

It is therefore no wonder that the rehearsals of this particular performance lasted six months and that when Tasos Dimas appears on stage as the Watchman, the viewer feels himself being transported to other rhythms and depths – which seem to be related to the quests of the Japanese Noh theatre. With the actors immersed in primitive memories of their own bodies, the show will narrate the tragic fate of the House of Atreides as it unfolds in Agamemnon, the Libation Bearers, and ultimately the Eumenides.

In Agamemnon, the great victor returns to Mycenae, only to have himself and the prophetess Cassandra killed by Clytemnestra, who, together with Aegisthus, will install a new tyrant in the city. Terzopoulos’s directorial choices in terms of presenting the Chorus as a collective that is adrift (a moment of great inspiration when the members of the Chorus are lined up and illuminated in a way that symbolizes the red carpet that King Agamemnon will cross to meet Clytemnestra, with the colour indicating the vicious cycle of blood) and of Clytemnestra as an archetypal femme fatale, catch the viewer’s attention. As the entire work has focused on, among other things, the placement-retraction of the actors’ vocal organ, there are moments when one freezes with the material that Sophia Hill as Clytemnestra draws out, in an effort that straddles the line between primordial matriarchy and the distortion of the world of patriarchy. Speaking of Cassandra, Evelyn Assouad is haunting in the way she evokes the sounds of the Orient and in the mournfulness that accompanies the musicality of her interpretation. In Agamemnon, as Theodore Terzopoulos imagined him, we get only a first glimpse of the teaching that followed in the Chorus; a perfect coordination of the actors, a positioning of a Body constantly trampled by power, and an inspired Exodus before the introduction to the Libation Bearers.

In The Libation Bearers, the slaves of the palace will join Orestes and Electra in the revenge they vow to take for the murder of their father. With the ritualistic element ever present in Terzopoulos’ approach, we are amazed at the flexibility of the Chorus, who changes formations and tones with virtuosity, while Konstantinos Kontogeorgopoulos as Orestes and Niovi Charalampous as Electra are overwhelming in their sense of rhythm during the scene of the recognition of the two sisters. The extended silences serve in this part of the terzopoulian approach as a kind of distancing, in order for the viewer to understand the crime of the crimes and the eye of fate that seals the House of Atreides and History itself.

After the murder of his mother and Aegisthus, Orestes flees to Athens – chased by the Furies. As for the entrance of the Chorus at the beginning of the Eumenides, Terzopoulos’ method again finds its target, as the sounds produced by the actors’ bodies take us centuries back and beyond this world. It is no coincidence that this entrance was applauded by the audience. In addition to the mysticism that the Eumenides evokes, it is also a high moment of the dialectic that develops in ancient tragedy-dialectic that is delivered intelligibly to the audience by Eleni Varopoulou’s well-balanced translation. The goddess Athena (it is hard for one to forget the monologues of Aglaia Pappa, however high she/he sat in the rows of the ancient theatre), establishing the Areopagus, and with the support of Apollo, who oracled Orestes to his tragic act, stands up against the Furies, ultimately condemning them to go “under the earth”. In this last part of the performance, Theodoros Terzopoulos’ ideological aim becomes even clearer, with the emergence of Athena as a kind of prototypical political orator, and with the condemnation of the Eumenides suggesting the distancing of “modern civilization” from anything that comes from the depths of human existence (hence Terzopoulos’ statement that psychoanalysis is one of the most appropriate ways to decipher the mysteries of ancient tragedy).

The Oresteia, which was first presented at the Dionysia Festival in 458 BC, continues to fascinate through the centuries with its myth and its political dimension. Theodoros Terzopoulos, a world-renowned director, joins the long list of directors who give their own reading on the myth of the House of Atreides. His systematic training of his actors and his choices (culminating in the non-use of microphones in the Epidaurian space) make his Oresteia a milestone in the performance of this play at the Ancient Theatre of Epidaurus.

Leave A Comment