The National Gallery – Alexander Soutzos Museum, in collaboration with MOMUS – Museum of Modern Art – Costakis Collection, presents the anniversary exhibition entitled The World of the Avant-Garde: City, Nature, Universe, Man, which marks the thirtieth anniversary of the first major presentation of the Costakis Collection in Greece.

The new exhibition at the National Gallery reexamines the Costakis Collection through the prism of the relationship between man and the environment, a theme that was a critical field of artistic research in Russia in the early decades of the 20th century. Through three themes, the exhibition highlights the transition from convention to experimentation, from convention to utopia, as art engages in dialogue with the political, ideological, and aesthetic quests of the era.

The three themes of the exhibition, City, Nature, and Universe, examine the relationship between humans and the constructed (City), the organic (Nature), and the unexplored space (Universe), highlighting the artistic pursuits of the Russian avant-garde between experimentation, technological progress, and utopia.

Collector George Costakis in his apartment on Vernadsky avenue. Photo by Igor Palmin. Moscow, mid 1970s.

The section on the City will present works that refer to a new organization of space and functional objects, through the emphasis on pure form and the minimalist use of materials. Modern times are changing the perception of beauty, while technology is changing people’s everyday lives. The aesthetics of Constructivism give rise to new proposals in architecture, graphic and industrial design, clothing, and practicality in life, which also influence gender relations.

The Nature section will feature works that refer to the perpetual motion and autonomous biological rhythm of the organic matter that surrounds humans on Earth. From the symbolic power of Nature that subjugates Man, to Nature as an integral part of life, the artists of the Organic School have set themselves the task of bringing Nature back into art, through observations and experiments that make it easier to understand how the image of a natural environment changes in relation to changes in light and temperature, and they incorporated organic movement and sound into artistic practice.

The section on the Universe will present works related to utopian explorations and the vision of getting to know “other places,” space exploration, and the representation of cosmic matter with elements that are both imaginary and scientific, leading to new worldviews and philosophical considerations about life and art. The approach to and understanding of the unseen side of the world, such as the infinite space of the universe, has a philosophical dimension that develops in artistic movements such as Suprematism and Cosmism, but also coexist with scientific approaches. The result of this coexistence creates explosive compositions in art.

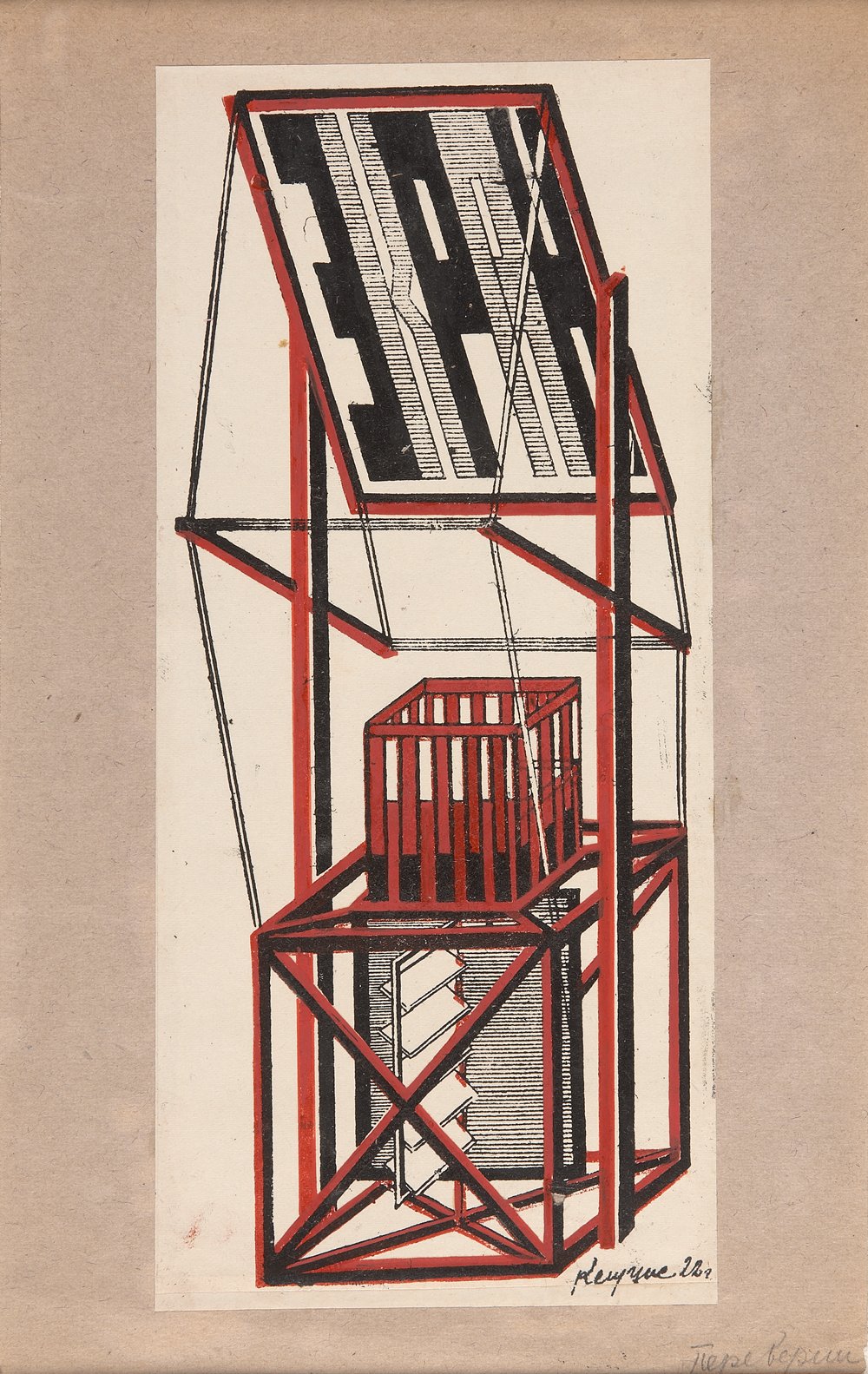

Gustav Klucis, Rujiena (Russian Empire, now Latvia) 1895 – executed Moscow (USSR, now Russia) 1938

Radio Orator. Agit stand with screen and speaker’s platform

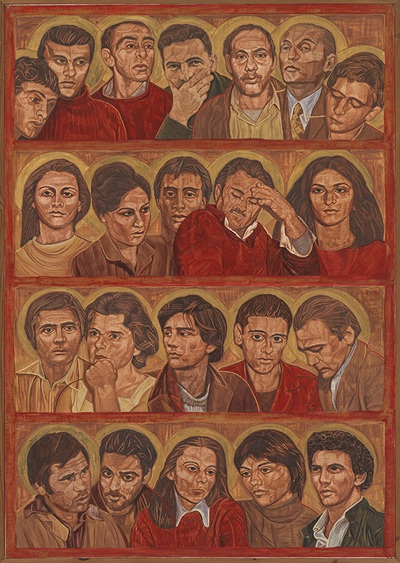

The section Man acts as a connecting link between the City, Nature, and the Universe. Man is at the center of the revolutionary and utopian proposals of the Russian avant-garde. Artistic experimentation is not limited to exploring the limits of human ability but seeks to expand the possibilities of those limits, aiming to improve everyday life and shape new visions for the future. The works on display highlight the relationship between art and consciousness, collectivity, science, and spiritual and philosophical inquiry, portraying Man as an active creator and participant in shaping the world around him.

About Russian Avant-Garde

Artists active in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union from the early 20th century to the 1920s did not use the term “Russian avant-garde” to describe the experiments and innovations they introduced into the arts. The word “avant-garde” was first used to refer to the vanguard of an army. The term (English translation: “avant-garde”) was first applied to the arts in France in the early 19th century; this usage is attributed to Henri de Saint-Simon. Although the term “Russian avant-garde” was first used ironically by Russian critic Alexander Benois in 1910, it became widely used in the 1960s by Western art historians in an attempt to find a term that encompassed all the groundbreaking movements, groups, and individual artists who, within the broader revolutionary thinking of the time, changed perceptions of aesthetics, form, and the relationship between art and life.

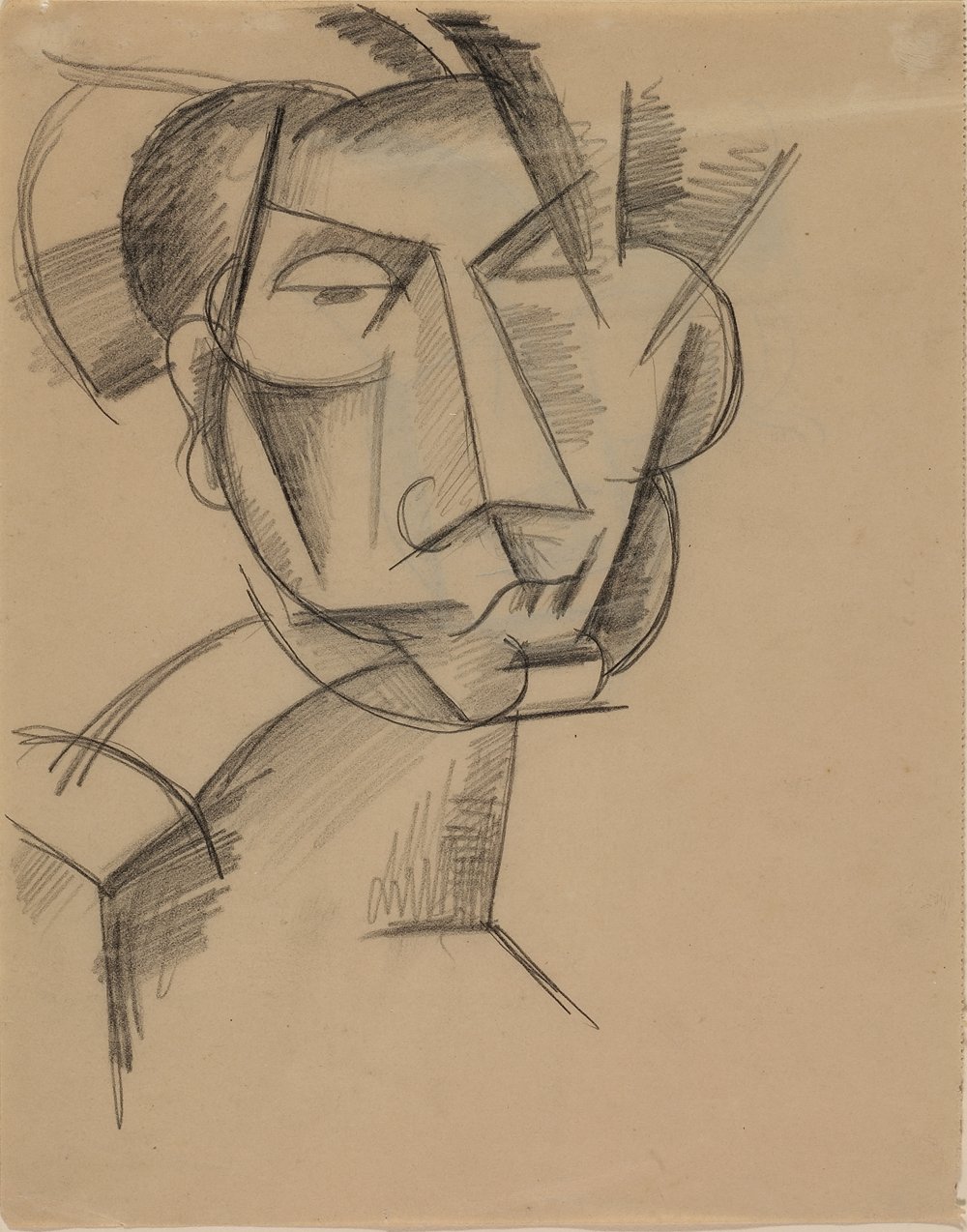

Liubov Popova, Ivanovskoe (Russian Empire, now Russia) 1889 – Moscow (USSR, now Russia) 1924

Study for a female portrait

1913

The term “Russian avant-garde” is by no means a national designation. It is a geographical designation that helps us understand that Moscow and St. Petersburg (formerly known as Petrograd and Leningrad) provided fertile, welcoming, and creative ground for artists from Russia, the Baltic states, Ukraine, and the Caucasus found a suitable, and took part in an extremely inventive, imaginative, and inspired dialogue on the arts, which was abruptly interrupted by the imposition of socialist realism and the persecution of artists in the early 1930s. This art also influenced artists living in other cities in the 1920s, such as Tbilisi, Kiev, Odessa, Kharkov, Tashkent, Yerevan, and Baku. For this reason, we can specify the geographical areas and use the terms “Ukrainian avant-garde,” “Georgian avant-garde,” “Central Asian avant-garde,” etc., always bearing in mind that the avant-garde experiment of the first three decades of the 20th century in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union had a strong multinational character.

About collector George Costakis

George Kostakis was born in Moscow in 1913. His father was a merchant from Zakynthos who had settled with his family in Moscow. He lived most of his life in the Russian capital and worked as a driver at the Greek embassy until 1940. When the Greek embassy closed due to the war, George Kostakis continued to work at the Canadian embassy. As part of his professional duties, he accompanied foreign diplomats on their visits to antique shops and art galleries. Without any particular artistic education or contact with modern art, but gifted with a rare instinct, he was impressed when he saw a painting by Olga Rozanova in 1946. From then on, he became interested in early 20th-century Russian experimental art. He contacted the families and close circle of the artists, as well as those artists who were still alive, and for at least three decades he methodically collected works of the “Russian avant-garde,” creating a renowned collection that saved this extremely important part of 20th-century European art from destruction and oblivion. In many cases, he faced particular difficulties because the Stalinist regime had banned the works of the Russian avant-garde, imposing the doctrine of socialist realism on art. He believed that the neglect of the art of the “Russian avant-garde” was a tragic mistake and that “people would need and appreciate it one day.”

In the 1960s and 1970s, George Kostakis’ apartment in Moscow was directly linked to the banned avant-garde art movement and functioned as an unofficial Museum of Modern Art.

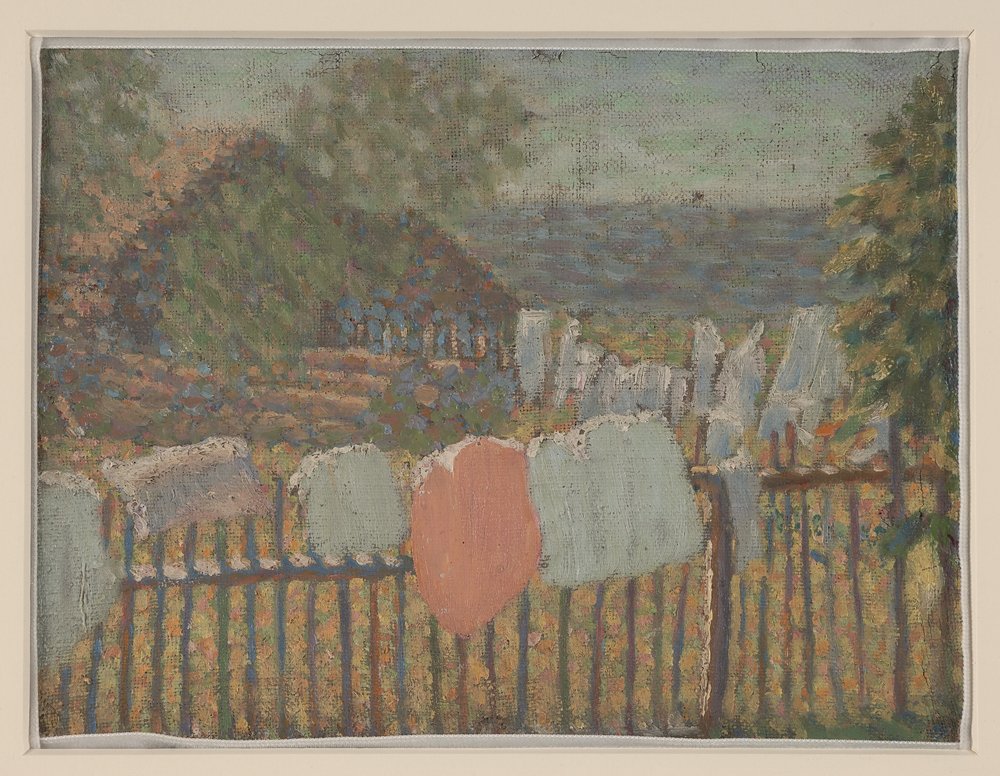

Kazimir Malevich, Kyiv (Russian Empire, now Ukraine) 1879 – Leningrad (USSR, now St. Petersburg, Russia) 1935

Landscape with

house

1905-1906

In 1977, Costakis left Moscow with his collection, leaving 834 works as a donation to the Tretyakov Gallery. After the first exhibition of his collection at the Kunstmuseum Düsseldorf in 1977, and especially after the exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1981, his collection toured exhibitions at major museums in Europe, the US, and Canada. George Costakis died in Athens in 1990.

In December 1995, the National Gallery – Alexander Soutzos Museum, curated by Anna Kafetsi, which sparked developments in the history of museum institutions in Greece.

The exhibition will feature works by the artists:

Babichev Aleksei, Bobrov Vassilii, Bubnova Varvara, Chashnik Ilya, Chekrygin Vassilii, Drevin Aleksandr, Ender Boris, Ender Ksenia, Ender Maria, Ender Yuri, Filonov Pavel, Grinberg Nikolai, Guro Yelena, Ioganson Karel, Kandinsky Vassily, Klucis Gustav, Kliun Ivan, Kruchenykh Aleksei, Kudriashov Ivan, Ladovsky Nikolai, Lissitzky El, Malevich Kazimir, Mayakovsky Vladimir, Matiushin Mikhail, Miller Grigori, Miturich Petr, Morgunov Aleksei, Nikritin Solomon, Puni Ivan, Plaksin Mikhail, Popova Liubov, Redko Kliment, Rodchenko Aleksandr, Rozanova Olga, Semashkevich Roman, Sofronova Antonina, Stepanova Varvara, Suetin Nikolai, Sulimo-Samuilo Vsevolod, Tatlin Vladimir, Udaltsova Nadezhda, Vialov Konstantin, Volkov Aleksandr.

General Director: Syrago Tsiara

Exhibition curators: Syrago Tsiara, General Director of National Gallery Greece, Maria Tsantsanoglou, Artistic Director of MOMUS

Architectural Design: Nadja Korbut-Kiril Ass

Production coordination: Irini-Daphne Sapka

Visual identity: DpS Athens: Dimitris Papazoglou, Aristomenis Tzanou

Leave A Comment