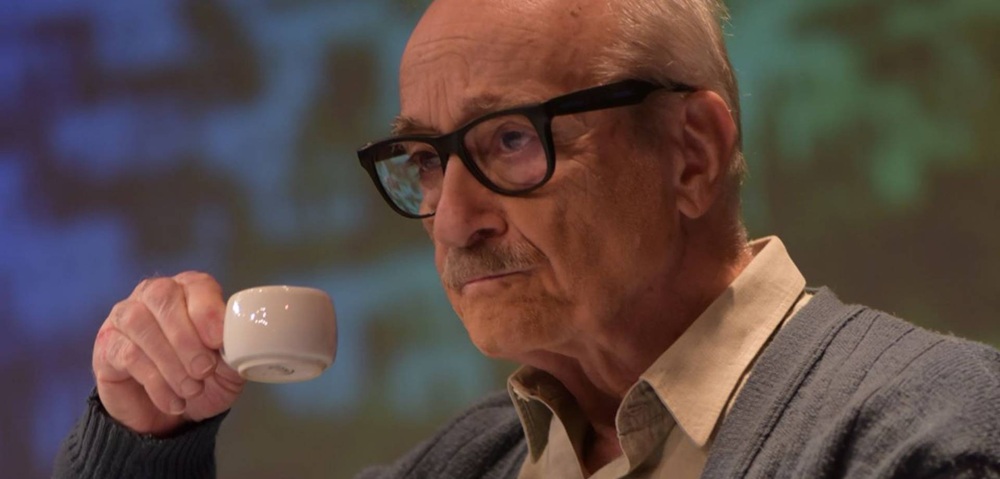

Thanassis Papageorgiou is undoubtedly one of the greatest performers in modern Greek theatre. Born in Kaisariani in 1938, he fell in love with both theatre and cinema at a young age.

Winner of the Koun Award and numerous other distinctions for his contribution to the arts and culture, the leading actor whom everyone enjoyed in plays by authors ranging from August Strindberg to Bost and Dimitris Psathas’s “Madame Sousou,” welcomed us with the kindness that has characterized his entire career in the theatre, which has been his home for the last 55 years.

This is the Stoa Theatre, which he personally manages, and where this year he is performing in and directing two plays that are different in genre but share a common ethos and the diligence that distinguishes him. Thanassis Papageorgiou talks to Days of Art in Greece about his artistic values, and of course Florian Zeller’s “The Father” and “My Mother’s Profession” (based on a story by Bost) which he is staging this year, in the fifty-fifth season that the Stoa Theatre is opening its stage lights.

Days of Art in Greece: In the motto of the Stoa Theatre, you refer to the “fraud of culture.” What exactly is this fraud, in your opinion?

Thanassis Papageorgiou:You will have noticed that the streets are full of posters advertising shows. Concerts, theatrical events, orchestras. Seeing all this, a stranger would say: “Culture is being produced here!” This is a facade. It is a well-established entertainment industry that makes a lot of money—some financially powerful people are involved for this very reason—but I don’t know how artistically inclined these people are.

This is fake, because we see that they do not produce art but spectacle—which is art’s worst enemy.

Many young and talented people also get involved in this process, either for publicity or for financial reasons, and have succumbed to various institutions that pretend to serve art, such as the Ministry of Culture. But damn them if they know what art needs and where, or how art addresses its audience.

D.A.: In the 1970s, you attempted to study film in Italy. What are your memories of that period? Are there any films that have inspired you in recent years?

TH.P.:At that time, in the absence of television, cinema was our only entertainment. We watched so many films back then that I can no longer watch any more. Let me explain: it’s not that movies aren’t good anymore, but I’ve learned the “formula” so well that I know what’s going to happen in the next shot. Seeing all those great actors on screen was part of our education. And then we would spend hours in the tavern—our second form of entertainment—talking about the movies we had just seen. Then we moved on to books, to Koun’s Theatre, and we began to wake up and see things more in terms of quality. In recent years, there have been films that have moved me, yes! When the market for art Iranian, Romanian, and Turkish cinema opened up, you couldn’t help but worship films like 4 Months, 3 Weeks & 2 Days by Cristian Mungiu, not to see that behind it all there is a vein throbbing, burning with its own blood.

From the Stoa Theatre’s productions

D.A.: You have worked with Ms. Leda Protopsalti in Bost’s major satirical works. Why does the current era seem hesitant towards comedy?

TH.P.: There are comedies, but they are very bad comedies, especially the ones on television, from what I hear. The same is true in the theatre. It is a “convenience” aimed at an audience that goes to the playhouse to laugh and “let loose” with shallow laughter, rather than with critical laughter. Unfortunately, the times we live in are not conducive to conclusions—they will leave no mark on the history of art. They will pass like a long parenthesis where nothing happened.

D.A.: In a recent interview with Myrto Loverdou, you mentioned that you believe in nature. Please explain a little how you approached Florian Zeller’s “The Father.” Through his story, do we feel the catalytic power of time and nature on the individual?

TH.P.: Nature is our womb. We cannot ignore nature!

By current standards, I am an “atheist,” but I believe in the omnipotence of nature. Nature is god, not some other entity with a name, a seal, and symbols. The play ends with the father saying that he feels like his “leaves are falling.” He feels like a tree that is “shedding.” What a beautiful metaphor from the author! Because that’s what happens when we slowly collapse in life. We feel like our hair, our fingers, our knees are falling off… And the audience responds because drama is cathartic—just as tragedy is cathartic.

D.A.: How do you feel about the audience’s response to “My Mother’s Profession”?

TH.P.: People laugh a lot, even though the play is bitter. So bitter that when I suggested it to Leda, she said, “I’m not playing that.” This play is like a knife. And the theater is packed, not only because the play is funny, but because there is a message behind the laughter. Note that the greatest dramatic actors are comedians. Chaplin was a very dramatic actor—you laugh at his mannerisms and the intrigue of the themes, but he himself was very dramatic at his core. Buster Keaton was the same. Even Roberto Benigni is terrifying. His dramatic moments in La Vita è bella were shocking. It’s no coincidence that you need to be good at drama to become a comic actor. Because what is comedy? Self-deprecation! And pain for the ugliness that surrounds us. As a viewer, you laugh, but inside you feel tense.

Thanassis Papageorgiou performs Florian Zeller’s “The Father” at the Stoa Theatre this year.

D.A.: What are the key points to keep in mind when adapting the works of great authors for the stage?

TH.P.:Basically, you have to understand the spirit of the author. So you don’t become a “translator-murderer.” It is very sacred to translate a phrase that cannot be rendered in your language. That is why I am strongly opposed to foreign directors coming to our country. There is no way that a foreign director can do meaningful work with foreign actors. If you don’t know the language, if you don’t know its rhythm, its harmony, its intonations, you can’t teach others. As for adaptations, in order for them to be successful, you have to be very unselfish, almost completely so. You have to say: “I will serve the writer and not myself.” Specifically, with Bost, you have to know his spirit and humor very well. He is very idiosyncratic. But I am happy to say that my humor is probably close to his. That’s why with “My Mother’s Profession,” even though it’s a work written essentially by me, when people come up to me and say, “Wow, what has this Bost written!” I feel that I have succeeded.

D.A.: What stage is modern Greek theatre at today?

TH.P.:It’s good, I think it’s good—within the context of the rusty epoch we live in, of course. I hear—because unfortunately I don’t have time to go to the theatre—that interesting topics are being written about, but how well the plays are written is another matter. In our time, when we staged Dialegmenos and Pontikas, good work combined with the writer’s serious anxiety produced a result. I don’t know how that happens at the moment. But I repeat—as long as this is the case—that the times are not conducive to conclusions; it is a bottomless pit. We have hit rock bottom, we are struggling to breathe and see what can be done from there on.

Thanassis Papageorgiou delivered a sweeping performance as Markos Vamvakaris in the play “I, Markos Vamvakaris.”

D.A.: Your name is associated with the virtues of dedication and hard work. Do you believe that these qualities are acquired or innate?

TH.P.:It is an innate element, that little bug you have inside you for art—just like we have thousands of others. But it needs to be cultivated! What is cultivation? Reading, studying… Are you an artist? Watch movies and go to the theatre. Are you an architect? Go out and look at buildings. Nothing can come solely from instinct. As for actors, if you study at the right school and truly understand what your relationship should be with the writer, the adapter, the costume designer, your colleagues, and the director, then you can create masterpieces. At Stoa Theatre, we follow another doctrine that has brought us great success: we do simple things. Because simplicity is the most difficult thing in the world.

If you ask an actor to perform like a fifth grader who has just been handed a little poem, it is impossible for them to do so. Why? Because they don’t have that innocence and gentle ignorance. I struggle a lot to achieve this as an actor, as a director, and as a team here.

I try to persuade actors not to do anything. “Say what you have to say from your heart.” The less you do, the better. But it’s very difficult. My other opinion is that the viewer should not understand that you are an actor “playing” something. Because then they watch your effort and not your meaning. You have to pass through the scene “invisible”.

Leave A Comment