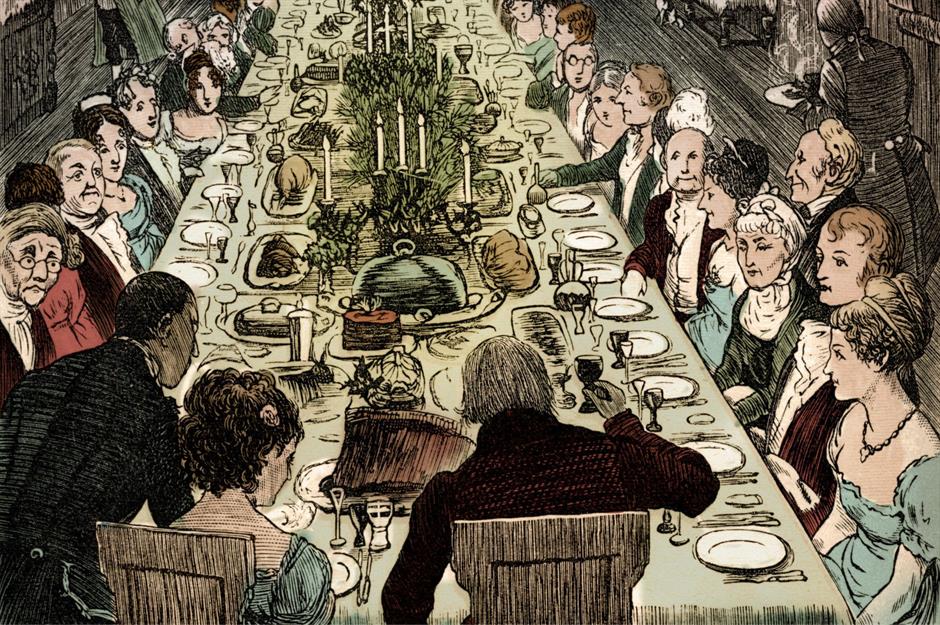

A decorated table full of food is the most universal symbolism of abundance, celebration and happiness. Christmas is perhaps the only, or at least one of the few, days in the year when the “good” cutlery and crockery will appear, the festive tablecloth will come out of the cupboard, mistletoe and candles will decorate the table.

Everyone’s memories of the Christmas days can only include the tastes, smells and of course the laughter, chats and even family arguments around the Christmas table. Very characteristic is the description of Kostis Palamas in Christmas:

Ah, ah, the Christmas table of the family

Where appetite matches love!

The little glasses sound sweet, the dishes sparkle,

Around the gray old age and youthful youth

A turkey in the middle, all hot and blushing, blushing, blushing,

and the wine runs everywhere, singing and foaming.….

and the grandfather’s indefatigable babbling begins,

a familiar and ancient Christmas story…

Already, from the first years that Christmas was celebrated, in Byzantine Constantinople, the city was decorated by the municipalities, the children sang carols and the inhabitants organized festive meals. Coexistence around the table became symbolic. As recorded by Liutprando of Cremona during his visit to the court of Constantine Porphyrogenitus, , the emperor, after the ceremonial mass in Hagia Sophia, returned to the palace where he provided a banquet for the lords, foreign guests and twelve poor inhabitants of the city.

At a similar royal banquet in England, King Henry VIII in the 16th century served turkey for the first time, replacing traditional dishes such as venison and pork. However, it took three centuries before turkey became widespread and became the traditional dish of British Christmas dinners. The ease of rearing and the size of the turkey, which could be sufficient for the members of a family, probably played a part in this. Charles Dickens in A Christmas Carol describes Scrooge’s ‘visit’ to his servant’s house in the Christmas Spirit of the Present. Suddenly, two little boys came running in. “We smelled a roast turkey! How nice! It smells from the street!” they shouted excitedly.”

In literature it is a common description of Christmas meals even for poor people, who forget the cold of December in the face of the warmth of the holiday: “As soon as Mass was over, they went home. The streets were filled with joyful voices. The doors of the houses were open and humming. The tables were waiting, laid with white tablecloths, with anything you could think of. The rich and the poor ate lavishly, because the lords sent everything to the poor. And instead of singing at the tables, they sang “Christ is born, praise you” (Fotis Kontoglou: Christmas Eve). And in another description of a rich meal, poor people, Kontoglou describes the table offered by “the chief shepherd John the Blessed, who, if you see him, you will think you are truly in the place where Christ was born. He’s an ancient man, innocent, with a black beard, like a saint. The clothes he wears are oriental shorts, on his legs he has wrapped shoes tied with strings, on his saddle he has a helmet and a bag. And the other shepherds are like John. The ones who sit on the sofa are visitors… So they sat around the sofa and ate. On the table were meats, unsalted cheese, manouri, agizia, fish, roasted snipe, and other birds of prey.

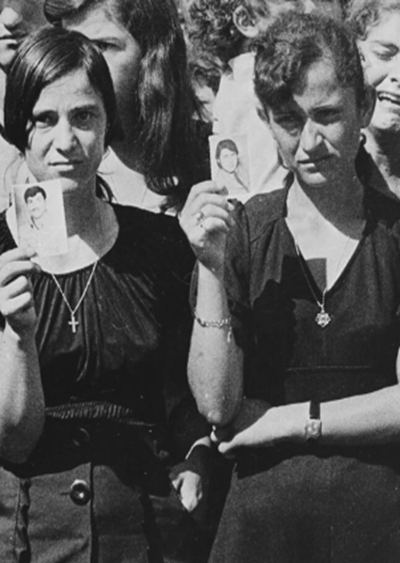

In the short story The Christmas of Thanasis Mertikas, the author Kostis Bastias describes the lonely Christmas of the immigrant Thanasis Mertikas, who found himself in a small American state on Christmas Day. The text, in a few pages, highlights the nostalgia, loneliness and solidarity of Greek immigrants, especially on a day like this: “The president of the community, together with the priest, invited him to the Christmas table.

– You can’t be alone for a festive night like this, they said.

And yet, for forty years he had been all alone, celebrating foreign holidays with foreign people. But he was unwilling and went.

When they arrived at the president’s house, they gave him things he remembered but had forgotten: ouzo, feta cheese, taramosalata, Kalamata olives and cheese pies. Silently he tasted everything. There must have been as many as twenty-five people at the table, from old people to children, and the priest in the middle, with the president on his right and Thanasis Mertikas on his left. All of them were eating gluttonously, talking, shouting, laughing and gesticulating. They talked a lot about Greece and especially about Kalamata, because all of them, except for Mertikas and the priest, were from Messina. The only one who didn’t talk, and who ate some turkey, was Mertikas. But deep down no one noticed. Every now and then, he was shouted at:

“Eat old man!…” “Courage, old man!…” “Eat old man!…”.

There are numerous examples in Greek and foreign literature where the characteristics of the Christmas meal are repeated again and again: the meal itself is just the occasion, the essence is none other than the camaraderie, the coexistence, the family atmosphere, perhaps the only celebration that generates similar feelings throughout time and the world.

Leave A Comment