Yiorgos Liaskos

Reading Room and Archival Research Department,

General State Archives of Greece – Central Service

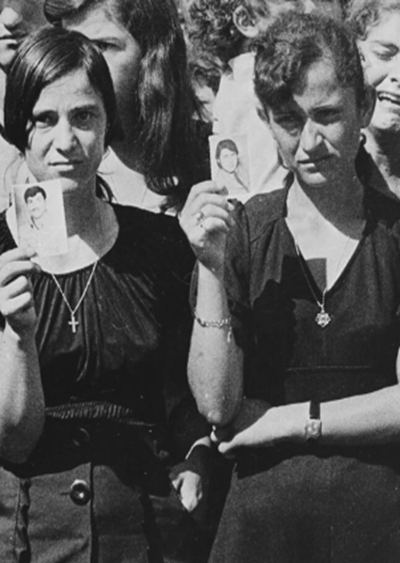

The Executive was one of the two Bodies, which came together and constituted the “Provisional Administration”, as established at the First National Assembly of Epidaurus in 1822, which declared the independence of Greece. A mere handful of documents from years 1823-1824, as compared to the huge volume of material available, can reveal all the episodes of a painful birth: the evolution of the old, multiform Romiosini into the modern Hellenism of the nation-state era. The place of the Revolution and the Genos/Nation of the Greek Christian Orthodox Romans/Romioi (as they were called in the language of the time) in all its diversity: Greek-speaking Muslims, Romioi/Greek Christians wearing the traditional foustanella/kilt, either Greek-speaking or Arvanitic-speaking (but also arvanitic speaking Turk-albanians). There were also the cosmopolitan Romioi/Greek in european dress, sometimes acting as agents of foreign embassies, Romioi/Greeks who were subjects of Russia or other countries, Romioi/Greeks subjects of England in the Ionian Islands, Ottoman Greek speaking Phanariotes, Cypriots and other volunteers of the greek diaspora, both well-meaning and deceitful philhellenes, Greek Catholics in Syros, etc.

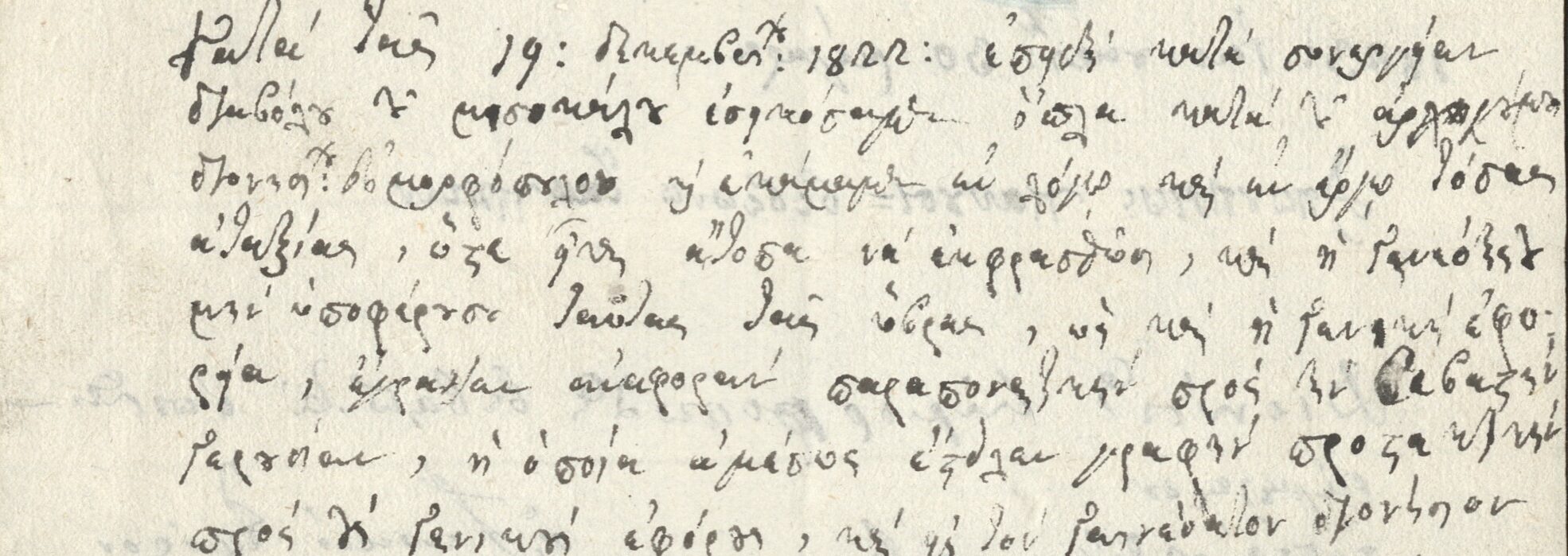

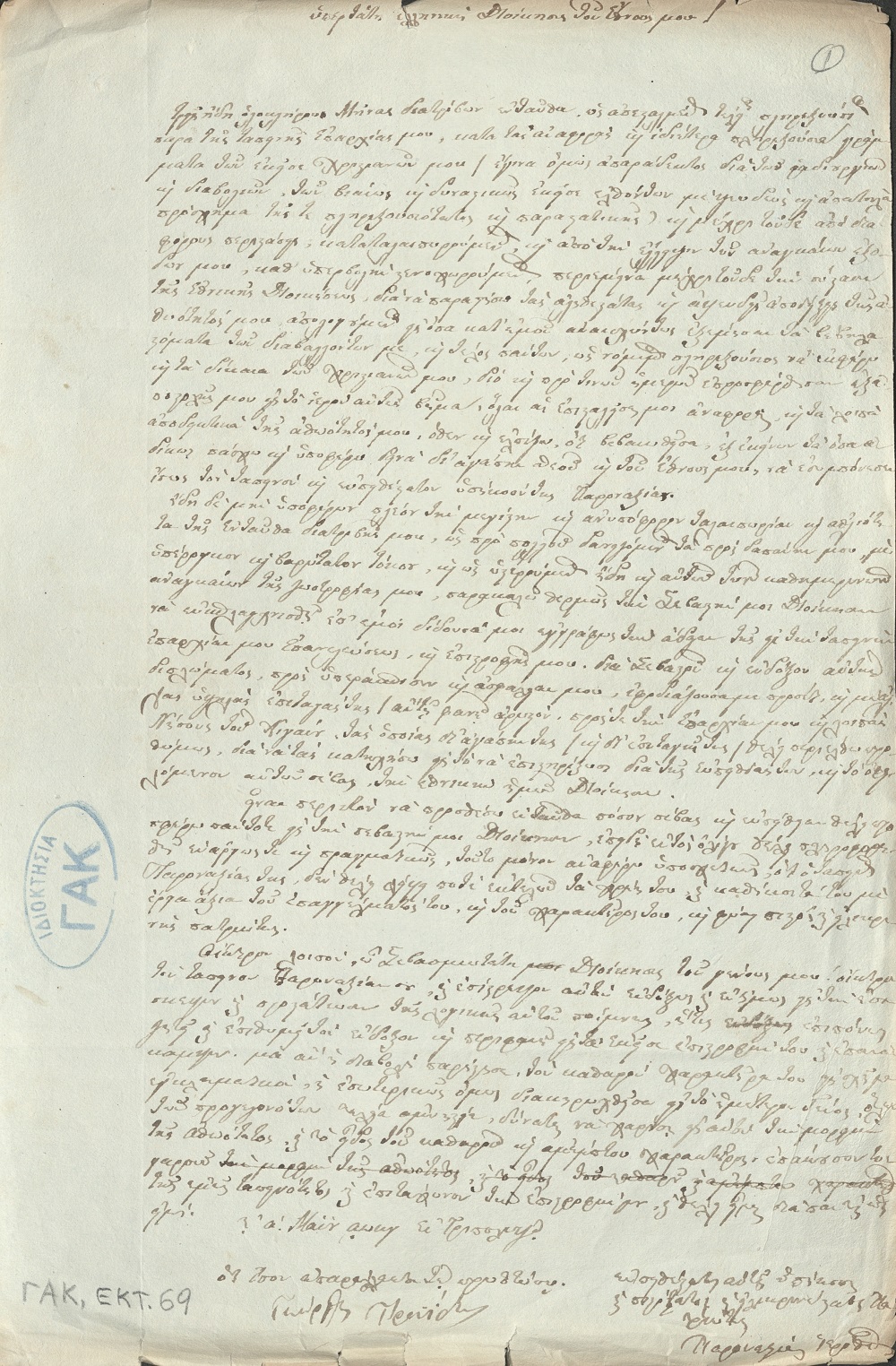

Letter of Megarees/General Bearers of Dervenochoria etc. to the Administration on the facts of civil disobedience (“…we have made a mischief…”). GSA, C.I., Executive f. file. 2 Doc. 37/1823 (1/2)

A whole world driven by a spirit of at times profound localism in the midst of both national triumphs and national divisions is simmering along in the same pot. Naturally, the severe daily material needs are omnipresent at the same time: we find numerous references to the purchase of the necessary grain, munitions and other necessities, as well as to taxation issues.

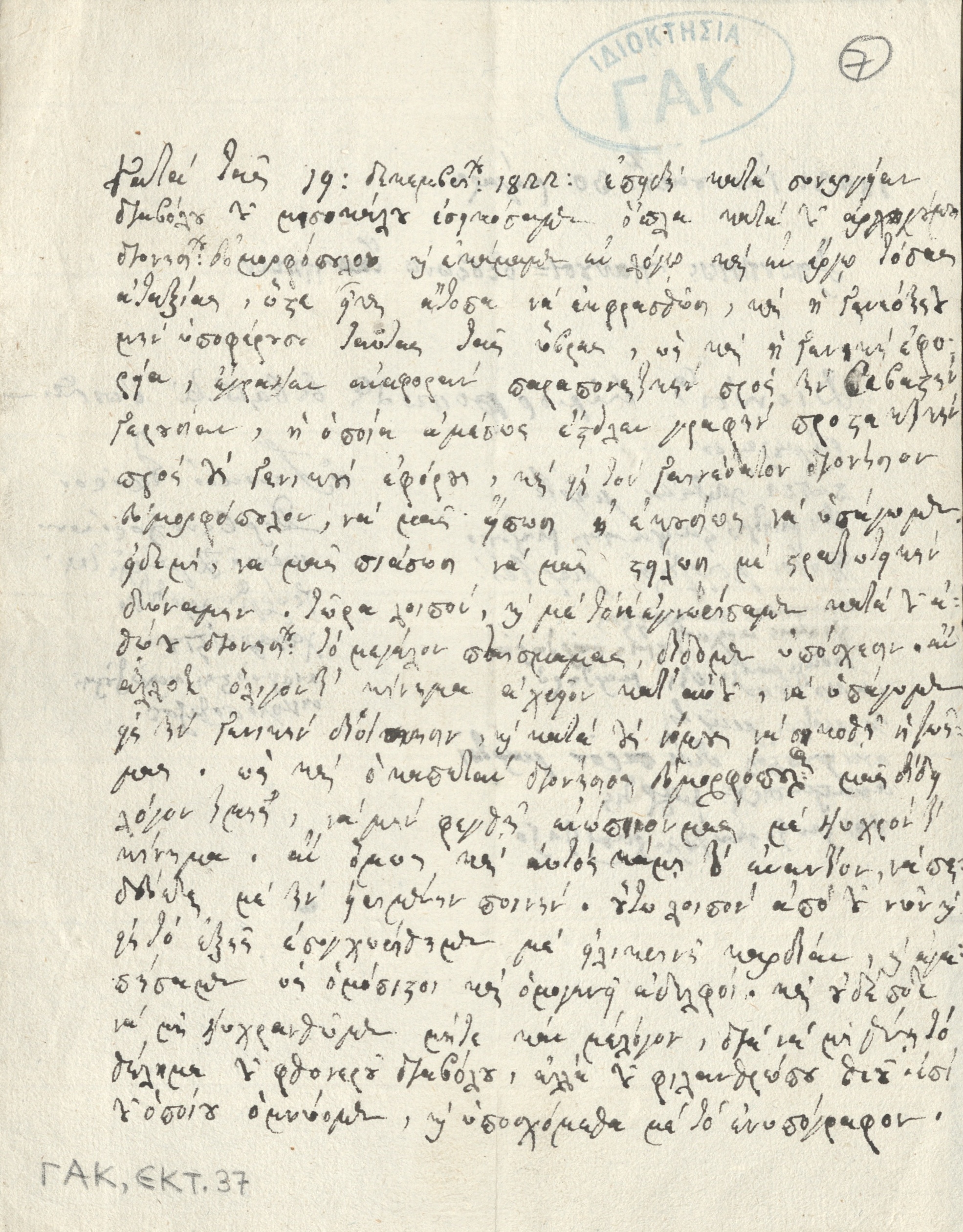

Letter of Megarees/General Bearers of Dervenochoria etc. to the Administration on the facts of civil disobedience (“we have made a mischief…”). GSA, C.I., Executive f. file. 2 Doc. 37/1823 (2/2)

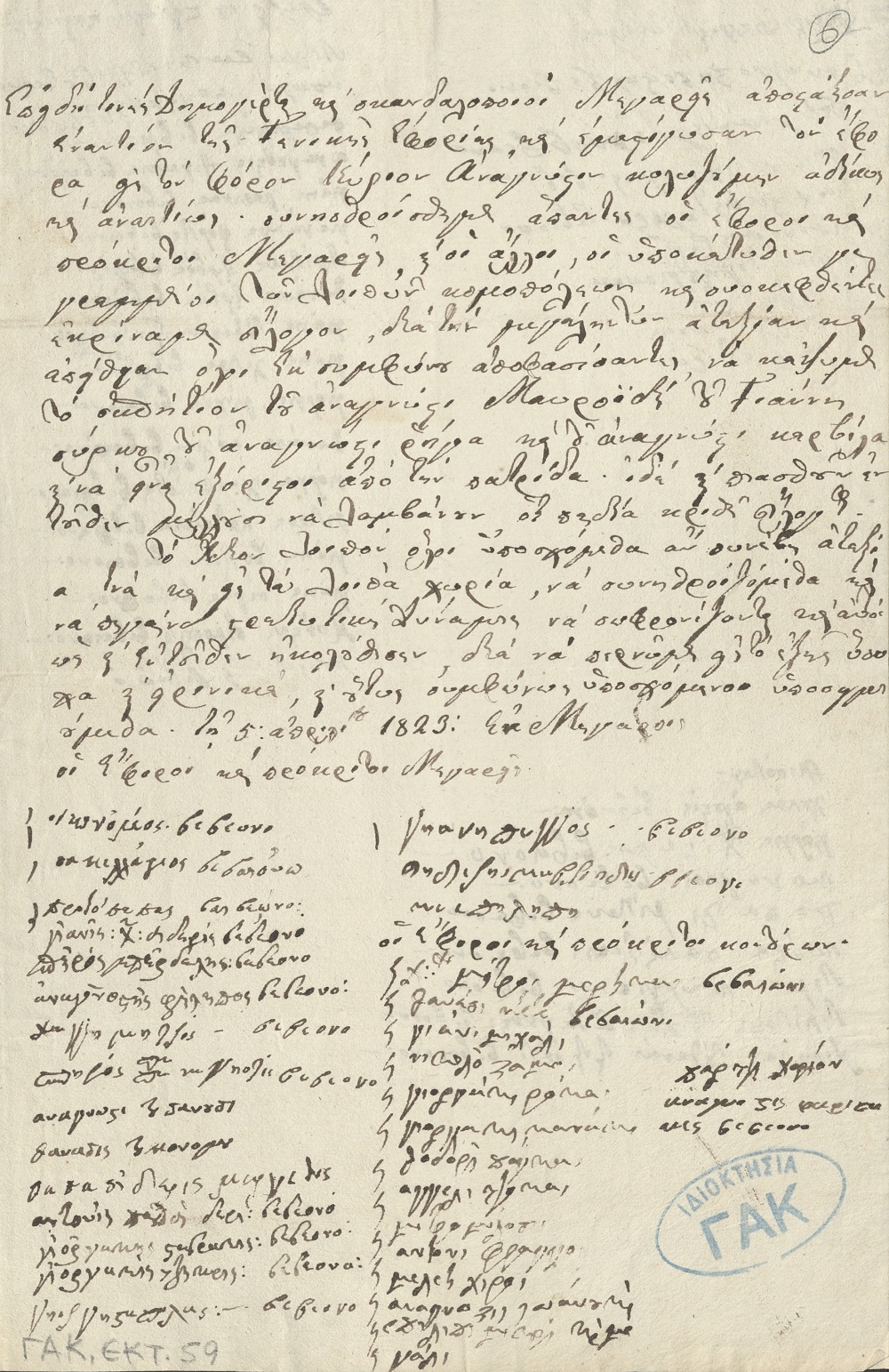

Once the Megarites (people of Megara) apparently refused to pay taxes and stood their ground against the tax collectors: “…some rabble-rousers and provoking Megarites”, the Executive Body’s 59/05-04-1823 document of the Megara dignitaries reads, “rebelled against the General Tax Office and whipped up the tax collector, Mr. Anagnostis Kalozoumis, unjustly and impudently”. In the same document the dignitaries of Megara relate that they in turn went on to burn the houses of the rebels and that the rebels, now exiled from Megara “…are to receive on the spot, if caught, whatever education may be deemed as appropriate…”.

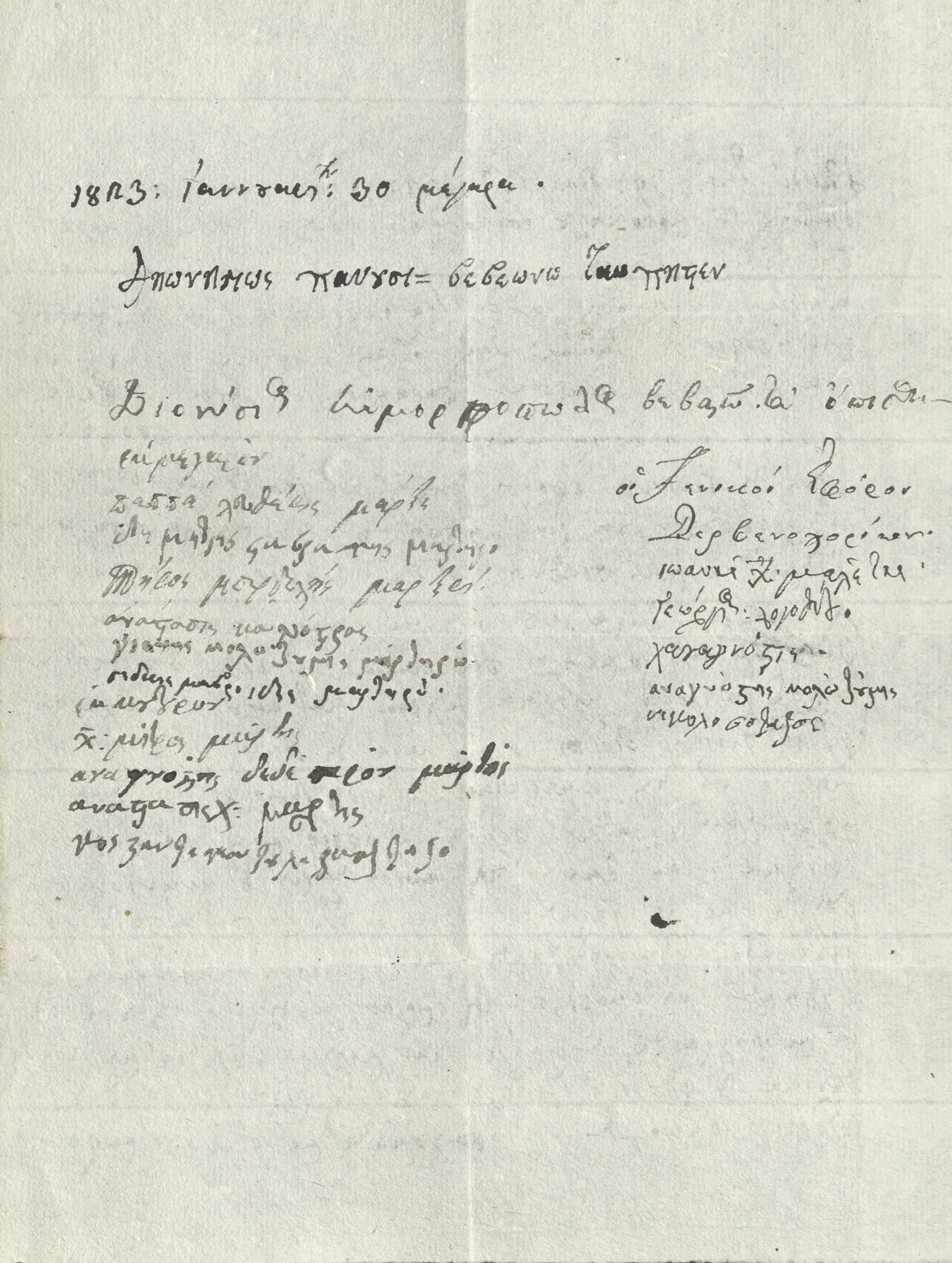

A letter with an undertaking for the maintenance of order signed by 65 ephors and procurators of the province of Megara. GSA, K.Y., Archive of the Executive File. 2 document 59/1823

“On December 19, 1822, because of our complicity with the devil, the good hating (anc.greek “μισόκαλος”), we raised arms against our leader Dionysios Eumorfopoulos, and caused such mischief, both in word and in deed, that it is impossible to describe, and his bravery, not suffering these insults, as well as the General Tax Office, wrote a report complaining to our respected Senate….” (Executive Body document 37/30 January 1823). In fact, this document is accompanied by a legally binding note promising “…that the above shall not be repeated”.

As regards the payment of taxes, the case of the Greek fishermen in Glarentza (Peloponnese, Ilia region), who came from the Ionian Islands closeby (under the British rule at the time), is different. To the request of the Greek revolutionaries to contribute to the Revolution, for being in an area controlled by the Revolution, the aforementioned fishermen appear to reply that they have no such obligation as they are English subjects.

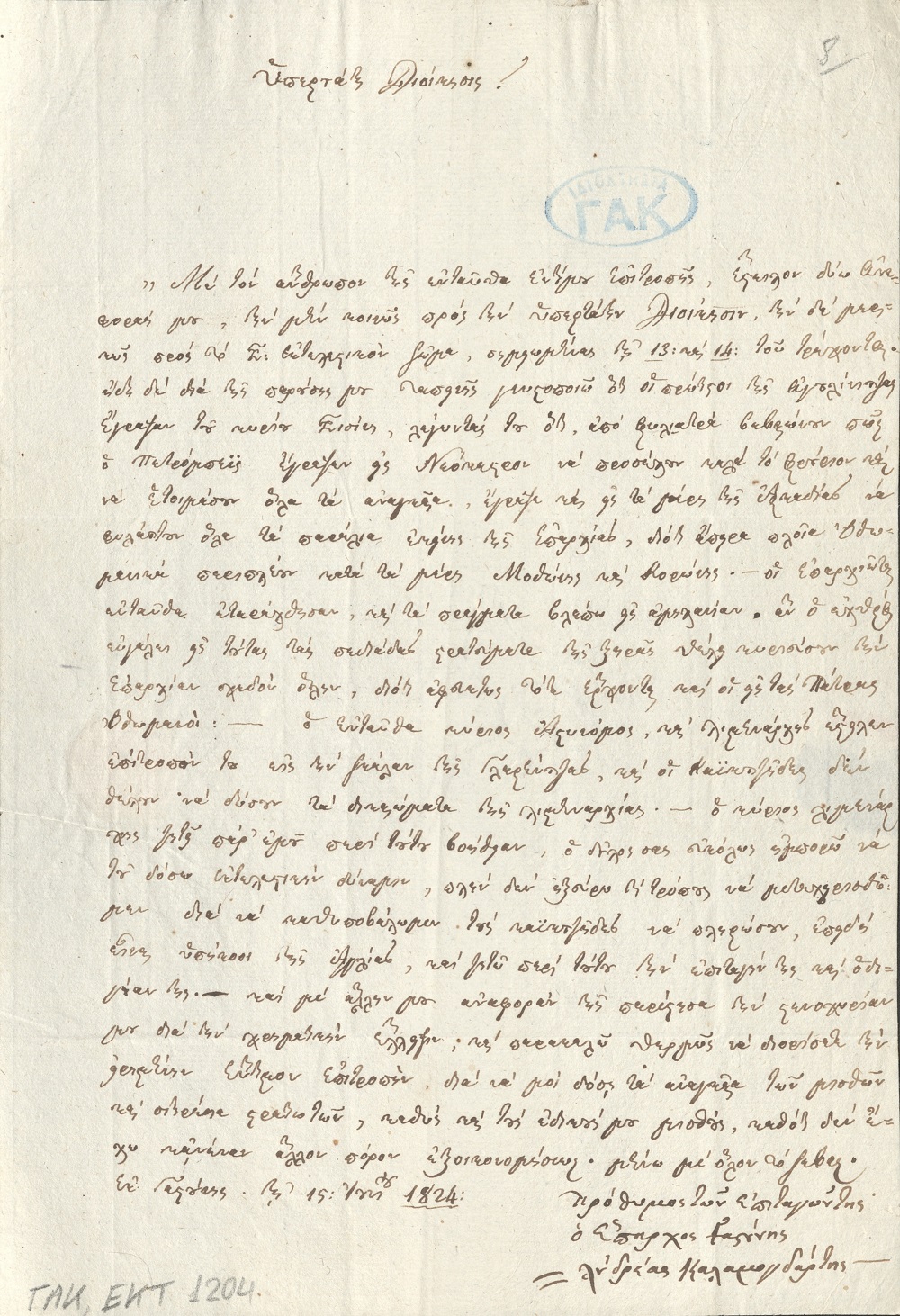

Metropolitan Ierotheos of Paronaxia to the Venerable Administration for what the… “those who are criticizing him “;. GSA, K.Y., Archive of the Executive, f. 2 document 69/1823

The prefect of Gastouni Andreas Kalamogdartes writing to the Administration in Nafplio on 15 June 1824 on the state of affairs mentions among others “that his province is in danger if the Turks move against it…,… that the fishermen in Glarentza refuse to pay the port taxes…”. He even adds that “this matter does indeed require delicate handling, because they happen to be English subjects” to conclude eloquently on his urgent material needs: “….as long as he is provided with the financial resources to carry out his ministry” (Executive Body document 1204/15-06-1824). An English citizen from Cephalonia (Ionian Islands), Andreas Metaxas was wounded in the same area in one of the first major military conflicts, in the battle of Lala, against the Turkalbanian clan of Lalaioi and a bounty was subsequently placed on his head by the English authorities declaring him a “terrorist”. Further down south in the region of Trifylia (Peloponnese), the local Christian clan of Dredes speaking the same language as the turkalbanian Lalaioi clan, were heroically fighting for the Greek cause…

At the same time the mundane life continues. Thus even complaints by some members of the flock against the clergy arise. There are letters to the Executive Body both for and against the Bishop of Paronaxia. His reply, written in a quite eloquent style and in the language of the time, is a pleasure to read: “…I have until this day patiently awaited the constitution of the National Administration in order to present the utterly truthful and irrefutable proofs of my innocence by defending myself against what the profane mouths of my critics have shamelessly spewed against me…”.

The Prefect of Gastouni A. Kalamogdartis to the Administration on the delicate issue of the taxation of the fishermen of Glarentza and other necessities. GSA. K.Y., Executive file, f. 10 document 1204/1824

The painful birth of the American nation and the subsequent civil war inspired a multitude of artistic work both in literature and cinema which in turn established the American national myth as both a grand spectacle and a worldwide cultural heritage. David Griffith’s film “Birth of a nation” (1916), is a typical example as well as starting point of such cultural production. This is not the case with the aftermath of the Greek revolution, given that the existing rich material remains unknown and rather misunderstood. Consequently it has never been properly researched and has hardly been under the Greek artists’ radar. However the transition of the multifarious Genos/Nation of the Christian Orthodox Romans/Romioi to the era of nation-states is reflected in this material. There is no good excuse why this transition in all its complexity, palpable in every aspect of human life, should still escape our attention, given that the evidence is here. This material offers a wealth of knowledge to effectively enrich our self-image and our self-awareness.

Drawing from this transitional and multi-layered historical moment, in the series of the adventures of the Greek space and the multi-dimensional Greek timeline and reality we can take a closer look at Glarentza of Ilia region mentioned above. Glarentza happens to be none other than the Greek paraphrase of Clarentia or Clarence of the Franks, an important fortified city and port of the Peloponnese during the Frankish occupation. It was built by the Villehardouins of the Principality of Achaia on the site of ancient Kyllini in the 13th century and served as the port of Andravida, the capital of the principality. In fact, the coins of the principality were marked DE CLARENTIA and later DE CLARENCIA. According to other sources, Glarentza may also have given her name to a title of nobility, the Duke of Clarence of England.

We may keep this in mind next time we visit the thermal baths of Kyllini or take the ferry to Zakynthos/Chephalonia.

Leave A Comment